“This piece is not for you. This is an unapologetic grasp for identity.”

So begins a new multimedia artistic work born out of an international exchange program called Digital Natives, which brought together a group of young Native American artists and those from African migrant communities in Belgium.

Last month, the eight artists gathered on a Native American reservation in New Mexico where, through workshops with artist-mentors, they explored how their displacement affects their cultures and identities. Those workshops culminated in the creative work titled Feeling Everything All at Once, which expresses their multiculturalism as well as the generational trauma they’ve inherited from their ancestors who were colonized and forced from their homes.

“We didn’t want to make a video that was talking about the past the whole time,” says Oriana Mangala Ikomo Wanga, a 21-year-old musician. Her parents came to Belgium from the country’s former colony, now the Democratic Republic of Congo, where they experienced traumas of which they still cannot speak. Ikomo Wanga believes it’s important for her generation to talk about those traumas, but she says, “We really wanted to make something contemporary that talks about how we feel now.”

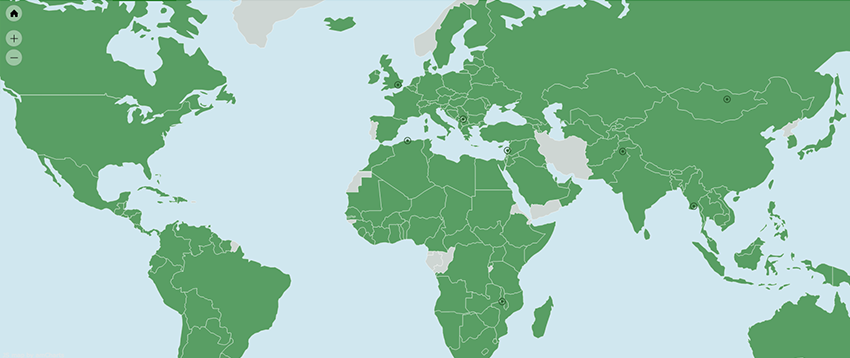

Digital Natives is part of Communities Connecting Heritage (CCH), a program sponsored by the U.S. Department of State with funding provided by the U.S. government and administered by World Learning. CCH engages underserved communities, empowers youth, and builds global partnerships through exchange projects exploring cultural heritage topics. Participating organizations and individuals partner up and submit proposals; selected partnerships receive funding and undergo a World Learning training course designed to help them manage the exchange.

For this exchange, CCH brought together Soul of Nations, an organization established to uplift displaced Indigenous communities throughout the Americas, and BOZAR, a distinguished international cultural center based in Brussels, Belgium. The organizations recruited Native American participants from the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and young people from African migrant communities in Brussels.

“It’s important to connect minority communities with other minority communities or Indigenous communities because they’re undervalued, underheard, and underserved,” says Soul of Nations Executive Director Ernest Hill. “[This exchange is] an alliance built on peace and unity.”

The exchange started virtually. In their first Skype session in October, each of the U.S. and Belgian participants shared an object with cultural, personal, or artistic significance. Gregory Ballenger, a student from IAIA, shared a traditional rug that he wove with his mother, a Navajo fashion designer. As Ballenger explained to his peers, his family had encouraged him to leave the reservation and pursue other opportunities. But being part of his colonizers’ culture made Ballenger realize he identifies more with the values of his own. Weaving the rug was an opportunity to reconnect with his roots.

“I look at that rug as a constant reminder of … how difficult it is to be a young Indigenous person who has been disconnected from his culture,” he says. “Weaving is not a man’s art — I shouldn’t be weaving in the first place, culturally — but that is one of the only ways that I have access to traditional art.”

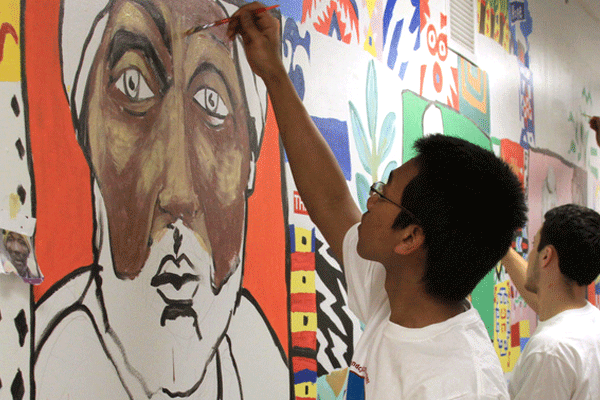

After their virtual introduction, the students met in person on a reservation near Santa Fe, where they took part in workshops with professional artists, created a print together using their own inked fingertips, and, through group discussions, shared their experiences with feeling displaced, alienated, and silenced by colonialism.

“We started to notice similarities and holes in our understanding of ourselves and how the lines of our identity become very, very muddy in the 21st century because we’re displaced from our original ancestral lands where we’ve lost languages, we’ve lost cultural teachings,” Ballenger says.

Ikomo Wanga agrees. This exchange program taught her that colonization looks similar no matter where it is carried out. She also noticed connections between African and Native American cultures, from the colors they use in their artwork to the importance of rhythm and music. “It was super mind-opening,” she says.

Those discussions fueled the multimedia project, which the group emphasizes is a personal account of the complexities they face as 21st-century displaced people — it is not meant to speak for their entire communities. In it, they assert their rights to their language and their lands, while describing the grief and uncertainty that comes with trying to bridge their native culture with that of their colonizers.

The artwork has already received recognition. On November 14, it was screened at a reception in Washington, DC, hosted by U.S. Senator Tom Udall from New Mexico as part of the Congressional Exhibition Project showcasing emerging Native American contemporary artists. It will premiere internationally in May when the U.S. students travel to Brussels to take part of BOZAR’s Next Generation, Please! festival. In the meantime, the exchange program will continue through virtual discussions and workshops.

Ikomo Wanga hopes the multimedia project will build awareness about the experience of being displaced from one’s culture and homeland.

“I would like to make people aware of what is happening still and that the past is not in the past,” she says. “It still has repercussions on us now.”