-

What We Do

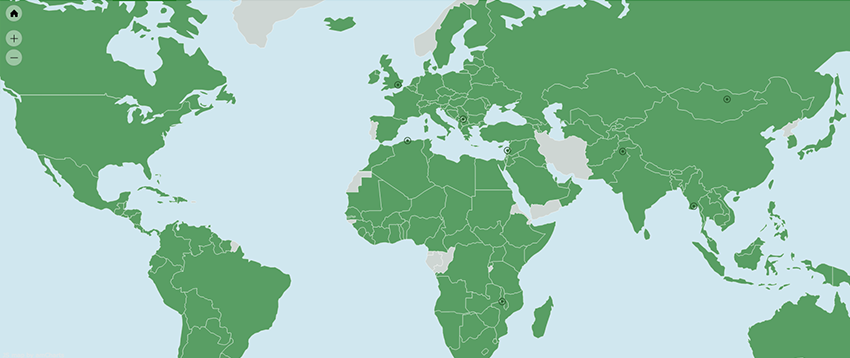

- WHERE WE WORK

-

About Us

Welcome Message from Carol Jenkins

Welcome Message from Carol JenkinsFor more than 90 years, World Learning has equipped individuals and institutions to address the world’s most pressing problems. We believe that, working together with our partners, we can change this world for the better.

On my travels, I’ve had the opportunity to meet with many of those who have joined us in this mission. In Baghdad, we’ve trained more than 2,300 Iraqi youth who are already giving back at home. In London, our partners in the TAAP Initiative strongly believe that we are all responsible to practice inclusion. And in Vermont, our Experiment in International Living and School for International Training participants prove every day that they have the tools and the determination to change the world.

Please join us in our pursuit of a more peaceful and just world.

- Get Involved

Media Center > Story

New Film Spurs Change in Mongolian Employment Practices

August 30, 2017

Unemployment is one of the most critical issues facing Mongolia today. Though it was once considered one of the world’s fastest growing economies, the country’s employment rate has risen steeply in recent years. Last year, nearly 12 percent of Mongolians were out of work.

But the situation is even more dire for certain segments of the population: according to Mongolia’s National Statistical Office, 30 percent of people aged 20 to 24 are unemployed, a figure that soars to more than 70 percent for people with disabilities.

A new documentary argues that Mongolia’s unemployment crisis cannot be tackled without acknowledging this disparity and the social inequalities that make it possible. On July 28, a team of emerging civic leaders premiered the film Journey to Job, which aims to raise awareness of these social and institutional barriers facing young people seeking employment. The film was the culmination of their participation in World Learning’s Leaders Advancing Democracy (LEAD) Mongolia program, which works with democracy advocates to spur change in their communities.

“Social inequalities are largely unknown and ignored in Mongolia,” says Ariunsanaa Batsaikhan, CEO of Maral Angel Foundation for Children with Spina Bifida. She contends that this lack of awareness only stigmatizes disadvantaged populations and ultimately impedes the country’s chances of economic recovery.

Journey to Job focuses on the stories of three people: Otgonjargal, a young deaf man and skilled carpenter who has been actively but unsuccessfully looking for a job for three years; Munkhzaya, a single mother who hasn’t been able to find employment since her daughter was born with a disability six years ago; and Otgontsetseg, a 16-year-old woman who recently migrated from rural Mongolia to Ulaanbaatar, where she works as a bricklayer to support her family. Their distinct experiences underline the ramifications of social inequality.

“Our society has so much stigma against these groups. They can’t find jobs and Mongolia’s employers are losing important talent,” Batsaikhan says. As the documentary illustrates, stigmatized groups — such as persons with disabilities or internal migrants — are quickly labeled “lazy,” “uneducated,” or “incapable” and may be barred from decent work. But that’s the wrong approach.

Instead, the film argues for social inclusion, which is the practice of including all people in public life. The team of activists learned about social inclusion through their LEAD Mongolia fellowship exercises like the Privilege Walk, which physically demonstrates how privilege works by asking participants to take steps forward and backward for each social advantage or disadvantage to see how they rank among their peers. “After taking these workshops, we wanted to speak for as many identities as possible in a really big way,” adds Ganzorig Dolingor, another LEAD Fellow and co-founder and chief editor of the popular news site Unread Today.

And in addition to that moral imperative, there is an economic argument for embracing inclusion: Citizens who are excluded from society cannot contribute to it. “There’s the threat of what we lose economically when we don’t include all groups,” Dolingor says.

Dolgion Aldar, executive director of the Independent Research Institute of Mongolia (IRIM), provided data and research for the documentary project. Aldar commends the group and argues that issues of poverty and unemployment should be topics of interest not only to academics and politicians, but to everyone in society. “Young leaders [like LEAD Fellows] are drivers of change,” she says. “It’s important for them to understand and acknowledge deeper social and structural constraints that prevent people from improving their lives.”

LEAD Mongolia Fellows participating in the Privilege Walk.

Working on the documentary did give the team greater insight into inclusion. “The LEAD program made me see the broader picture,” Dolinger says. The team itself was composed of leaders from deaf advocacy and LGBT rights groups. They’re from rural areas as well as urban. Dolingor says that diversity made Journey to Job better: “When we include more groups [in our projects] we can have more impact. We can make more change.”

Now that the documentary is complete, the group will circulate Journey to Job widely to raise as much awareness as possible. “We want to show it to many target groups, especially corporate businesses,” says Enkhjin Selenge, one of the team leaders. Ultimately, the aim is to convince employers to hire talent from disadvantaged groups. “We want to make an impact on hiring practices,” Selenge says. “If companies start hiring disadvantaged groups, then we succeeded.”

There is already a glimmer of hope. Several LEAD Fellows are initiating conversations with their own employers about inclusive hiring: Selenge’s employer, Toyota Mongolia, plans to revise the company’s hiring policy and will soon hire its first-ever person with a disability, while the construction company where Batsaikhan works when not involved in civil society just hired a former convict and a deaf welder. The team also shared Journey to Job with department heads from Ulaanbaatar’s Municipal Employment Office as well as with Oyu Tolgoi, one of the largest private sector employers in Mongolia.

But their advocacy journey is just beginning. “We need to do more to raise awareness,” Selenge says. “This documentary is just one step.”

LEAD Mongolia is a World Learning program funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), which is working with some of Mongolia’s best and brightest emerging democracy advocates. LEAD Fellows represent all different sectors of society, but they have a common ambition to spur positive change on the issues they care about most.

Written by LEAD Mongolia Project Director Adam LeClair