-

What We Do

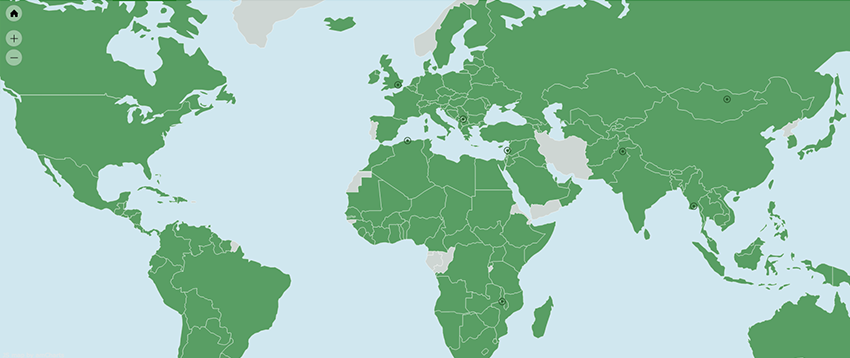

- WHERE WE WORK

-

About Us

Welcome Message from Carol Jenkins

Welcome Message from Carol JenkinsFor more than 90 years, World Learning has equipped individuals and institutions to address the world’s most pressing problems. We believe that, working together with our partners, we can change this world for the better.

On my travels, I’ve had the opportunity to meet with many of those who have joined us in this mission. In Baghdad, we’ve trained more than 2,300 Iraqi youth who are already giving back at home. In London, our partners in the TAAP Initiative strongly believe that we are all responsible to practice inclusion. And in Vermont, our Experiment in International Living and School for International Training participants prove every day that they have the tools and the determination to change the world.

Please join us in our pursuit of a more peaceful and just world.

- Get Involved

Media Center > Story

How One Team of Activists Is Making Transparency Inclusive in Mongolia

July 20, 2017

Transparency hinges on the concept of inclusion: By bringing the general public into discussions about systems of governance, society can root out corruption and hold leaders accountable. But a group of up-and-coming anti-corruption advocates in Mongolia argue that current transparency efforts aren’t inclusive enough.

“Without inviting different groups of society [to help solve a problem] we miss out on certain [points of view],” says Bilguun Batjargal, an Ulaanbaatar-based lawyer. “Yes, you can avoid exclusion. Yes, you can avoid being discriminatory. But it’s not enough.” To be truly inclusive, all communities need to be brought into conversations about corruption and transparency.

Batjargal and a group of 10 other emerging anti-corruption leaders are working with World Learning on a transparency project that employs these principles of social inclusion. The Transparent and Accountable School project aims to rebuild trust between the schools and community of Ulaanbaatar’s Nalaikh District, an underserved area on the outskirts of the capital.

Trust is sorely lacking in that relationship. Nominchimeg Davaanyam, an education specialist and NGO leader working on the Transparent and Accountable School project, says administrators discourage parents from getting involved in school budgeting and planning issues. Teachers and students, too, are shut out. Davaanyam argues this only allows corruption to flourish, which she worries will erode trust in Mongolia’s democratic transition and discourage the next generation. “If young people start accepting [corruption] as a norm, then we are doomed,” she says. “They need to be educated on topics related to anti-corruption and transparency.”

The project team wants to address this dearth of transparency by providing a platform for teachers, parents, and students to get involved and to realize they have the power to do something about corruption. The intent is to build transparency and trust through public participation in school planning, budgeting, and other processes. Through a series of trainings, the team is helping the community create their own transparency plan for the school.

Selection of the Nalaikh District was an intentional act of inclusion. The area has a sizable Kazakh community — the largest ethnic minority in Mongolia. The project group crafted a design to include the Kazakh community, ensuring Kazakh language interpreters were present at all activities and translating content into both Kazakh and Mongolian languages.

But the transparency project takes inclusion even further than that: Instead of simply bringing the obvious stakeholders — like parents and teachers — into the conversation, the Transparent and Accountable School project is engaging everyone from students to school janitors. “We wanted to include all layers of the school community, not just the school administrators, but also the people who clean the school,” Davaanyam says. The team argued that if certain groups aren’t included, there’s a greater risk for corruption.

The Transparent and Accountable School project team came to see the importance of social inclusion as participants in World Learning’s Leaders Advancing Democracy program (LEAD Mongolia), which works with some of Mongolia’s best and brightest emerging democracy advocates. In partnership with the U.S. Agency for International Development, LEAD Fellows visit the U.S. to take part in intensive trainings, then implement group projects in groups tackling issues like poverty, youth unemployment, the environment or, like this group, transparency and corruption. Inclusion, a core value of World Learning, was the subject of several of the group’s training workshops.

“A year ago, I wouldn’t have considered that inclusion would play a big role in transparency or anti-corruption. I thought of it as just trying to raise awareness on the issue of corruption itself and that’s it,” Davaanyam says. “[The workshop] really allowed me to think differently about how we exclude or include different groups of people.”

In turn, the Transparent and Accountable School project has encouraged members of the Nalaikh community to think differently about how they can contribute to the school. As a community-owned model of democracy, the program demonstrated that all voices matter and should be included in discussions about the school’s future. “It opened the horizons of everyone involved,” Davaanyam says.

Batjargal agrees. He recalls the moment when the Nalaikh school cleaner, who took part in all the team’s trainings, delivered a speech at their project closing event. This level of involvement — from school principal to school cleaner — is uncommon in Mongolia. “She felt empowered,” he says. “She realized she can do more than just do her job. She can part of the process and have a voice in the process. She can be part of so much more.”

That is truly social inclusion in action.

In August 2016, LEAD Mongolia piloted World Learning’s TAAP — Transforming Agency, Access and Power — Inclusion Initiative, a systematic analytical approach to integrating inclusion throughout a project life-cycle by “tapping” in to the voices, skills and experiences of all people, including those marginalized and excluded from power. LEAD Mongolia is the first project to commit to and employ the TAAP Approach and Toolkit to embed inclusion sensitivity in all aspects of the project life-cycle. The TAAP approach seeks to ensure that both World Learning’s LEAD Mongolia team as well as our participants have the skills to become practitioners of inclusive development. The LEAD team’s Transparent and Accountable School project is an example of this and illustrates the potential of supporting inclusion champions the world over.

Written by: LEAD Mongolia Project Director Adam LeClair