-

What We Do

- WHERE WE WORK

-

About Us

Welcome Message from Carol Jenkins

Welcome Message from Carol JenkinsFor more than 90 years, World Learning has equipped individuals and institutions to address the world’s most pressing problems. We believe that, working together with our partners, we can change this world for the better.

On my travels, I’ve had the opportunity to meet with many of those who have joined us in this mission. In Baghdad, we’ve trained more than 2,300 Iraqi youth who are already giving back at home. In London, our partners in the TAAP Initiative strongly believe that we are all responsible to practice inclusion. And in Vermont, our Experiment in International Living and School for International Training participants prove every day that they have the tools and the determination to change the world.

Please join us in our pursuit of a more peaceful and just world.

- Get Involved

Media Center > Story

Exploring Maryland’s Maritime Heritage By Living It

November 9, 2018

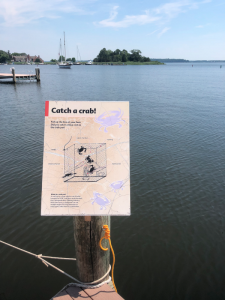

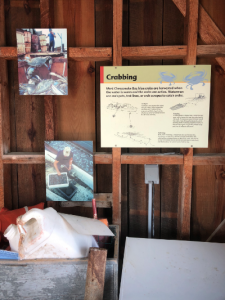

The Waterman’s Wharf exhibit sits isolated in the middle of a dock on the far side of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum grounds. The museum, which is spread along the shore of the Chesapeake Bay in downtown St. Michaels, Maryland, is primarily made up of open-air exhibits like this one.

I walked into the small wooden structure and found myself in a setting that was profoundly familiar: I could hear the breeze rustling the tall grass that filled the shallow water just outside the shack. I noticed the open crab pots on the ground, the tubs full of blue crabs in various stages of molting, and the old photos of watermen on the walls.

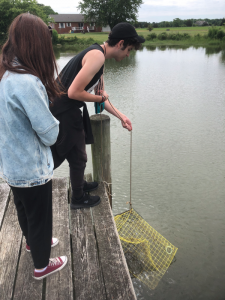

Just a few days earlier I was pulling a crab pot to the surface from the side of another dock. I was scooping “peelers” and “busters,” both names for stages of blue crab molting, out of climate-controlled tubs. I was on a Skipjack shaking hands with men just like the ones in the photos.

I realized then that I had not only learned about the cultural heritage of the Chesapeake Bay, I had experienced it for myself.

In June 2018, I spent three weeks traveling with Saving What Matters, one of six projects that I was working with on World Learning’s Communities Connecting Heritage program. This program brings together U.S. and international organizations and participants to explore cultural heritage. Participating organizations partner up and submit proposals for unique cultural heritage projects they will carry out together through both virtual and in-person exchanges. Selected partnerships receive funding and undergo a training course in which World Learning helps them build their capacity to manage such an exchange program.

Our partners on Saving What Matters were Coastal Heritage Alliance, an organization devoted to preserving traditional fishing family culture based in St. Michaels, Md.; and Cultural Heritage without Borders, an organization dedicated to preserving cultural heritage in areas affected by conflict in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. They developed a project exploring their cultural heritages by way of digital storytelling. On the Bosnian side, they focused on a special kind of pottery that only one man in one village still knows how to make. In Maryland, the participants focused on the people that still live traditional watermen culture in the Chesapeake Bay.

As part of the Saving What Matters project, a group of Bosnian students from the University of Sarajevo and American students from Goucher College in Towson, Maryland, first developed digital stories of their local cultures over the course of a six-month virtual exchange. They then participated in two in-person exchanges in which they visited one another’s countries, exploring their partner’s cultural heritage.

One critical element of the project was its emphasis on experiential learning. As cornerstone of World Learning’s teaching philosophy, Communities Connecting Heritage teaches our partners about the importance of experiential learning throughout their capacity building course.

One critical element of the project was its emphasis on experiential learning. As cornerstone of World Learning’s teaching philosophy, Communities Connecting Heritage teaches our partners about the importance of experiential learning throughout their capacity building course.

Experiential learning encompasses both learning by doing and learning by processing. In the experiential learning process, a participant first takes part in an activity, then is encouraged to reflect on the experience, taking time to understand what actions they took and how it affected them. Next, the participant begins to analyze the activity, exploring how it connects to their past experiences, and finding deeper meaning in it for themselves. Finally, the participant applies what they’ve learned through that experience throughout their lives.

While accompanying Saving What Matters in Maryland, I saw our partner, Mike Vlahovich of Coastal Heritage Alliance, emphasize experiential learning every step of the way. Instead of spending all of our time in museums, though there were some wonderful ones, we ventured outside to learn from the people who still live their heritage every day.

While accompanying Saving What Matters in Maryland, I saw our partner, Mike Vlahovich of Coastal Heritage Alliance, emphasize experiential learning every step of the way. Instead of spending all of our time in museums, though there were some wonderful ones, we ventured outside to learn from the people who still live their heritage every day.

We visited facilities where a staff of just two or three people work from early in the morning adjusting sprinkler intensity for tubs of blue crabs to simulate the natural conditions in the bay that encourage molting. Harvesting crabs right after they shed their old shell is how we get soft shell crabs, and the process requires great attention and care. We helped clean and paint the deck of a Skipjack, the traditional boat used for oystering in the Chesapeake Bay. We took a boat around Smith Island, observing firsthand how rising sea levels are eroding the shores of this small group of isolated islands. Instead of being told about the traditional way of life in the Chesapeake Bay, our participants were able to feel, smell, taste, hear, and see how these communities are preserving the maritime cultural heritage of the bay in their day-to-day lives.

Mike consistently emphasized the importance of not enclosing cultural heritage in a museum, but celebrating it and preserving it where it already exists. Academically I understood this, but I did not fully grasp what it meant until I was walking around the Waterman’s Wharf exhibit in the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Let me show you what I realized. Below are a few sets of side-by-side photos. The photos on the left are what I saw in the museum exhibit, while the photos on the right are what those exhibits sparked in my memory from our time spent experiencing maritime cultural heritage:

Crab pot simulation at the museum (left) versus pulling up a crab pot on the shore of the bay (right).

Sample soft shell crab facility in the museum (left) versus a real facility on the Eastern Shore (right).

Old photo of watermen crabbing in the museum (left) versus a local tradition bearer of watermen culture holding a basket of blue crabs (right).

This project challenged participants to think about cultural heritage as something to be preserved where it currently exists. They went beyond the classroom to see the world as it is. The participants of this program not only learned about the culture of the Chesapeake Bay, but had the privilege to walk alongside local tradition bearers for two weeks and experience it for themselves. My colleagues and I hope they will take the lessons they learned and reflected on along the Eastern Shore and apply them in their lives as they continue to celebrate and preserve cultural heritage back home.

They seem determined to do so. “My exchange program showed me how much heritage is being lived in the world of today,” says Jasmina Ferhatovic, a participant from Bosnia and Herzegovina who came to the Eastern Shore. “We are part of this heritage and its future. That is why heritage preservation is important, for both the people that live it and the people that study it.”

Sean Mooney is a program officer at World Learning.