-

What We Do

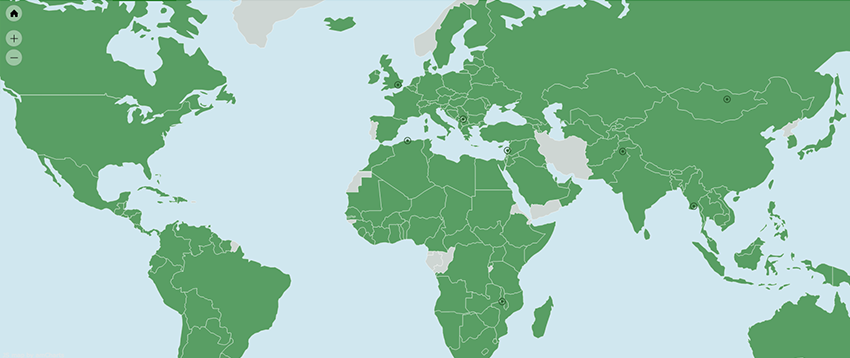

- WHERE WE WORK

-

About Us

Welcome Message from Carol Jenkins

Welcome Message from Carol JenkinsFor more than 90 years, World Learning has equipped individuals and institutions to address the world’s most pressing problems. We believe that, working together with our partners, we can change this world for the better.

On my travels, I’ve had the opportunity to meet with many of those who have joined us in this mission. In Baghdad, we’ve trained more than 2,300 Iraqi youth who are already giving back at home. In London, our partners in the TAAP Initiative strongly believe that we are all responsible to practice inclusion. And in Vermont, our Experiment in International Living and School for International Training participants prove every day that they have the tools and the determination to change the world.

Please join us in our pursuit of a more peaceful and just world.

- Get Involved

Media Center > Story

SHERR program convenes higher education, refugee resettlement agencies to work together

November 30, 2023

By Abby Henson

With an increased number of refugees arriving in the United States each year, representatives from all 10 national refugee resettlement agencies met earlier this month with more than 65 higher education institutions, federal and state agencies, and nonprofits to develop ways U.S. colleges and universities can help.

The number of refugees entering the country has more than doubled over the past three years, and the U.S. Department of State has set a goal to resettle 125,000 more in 2024 — a 30-year high if achieved. To meet the resettlement demands, the group convened for a two-day workshop organized by the program Supporting Higher Education in Refugee Resettlement (SHERR). The goal was to identify innovative ways colleges and universities can help resettle both student and non-student newcomers.

“As pillars within their communities, higher education institutions have incredible potential in this context, especially if schools join forces with resettlement agencies and experts in their communities.”

“We are excited about the opportunity to bring more people to safety and freedom,” said Holly Herrera, section chief of domestic resettlement for the Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM). PRM funds SHERR, which began in February 2023 and is led by World Learning in partnership with the Presidents’ Alliance on Higher Education and Immigration, Welcome.US, and the Ethiopian Community Development Council.

“We understand that higher education institutions, even with your vast ecosystems, face constraints,” Herrera said to the group. “What we aim for with SHERR, with the various partners under this umbrella that are involved in bringing together higher education institutions with resettlement organizations, is that more can be done. We want you to be bold. We want you to break glass. We want you to be consequential.”

“Refugee resettlement depends on a whole-community approach,” said Carol Jenkins, World Learning CEO. “As pillars within their communities, higher education institutions have incredible potential in this context, especially if schools join forces with resettlement agencies and experts in their communities.”

The workshop, held at the University of Maryland, College Park, and attended by its vice president of student affairs as well as the presidents of Guilford College and Bunker Hill Community College, highlighted language learning tied to career development, housing, educational opportunities, and service learning. Matt Brown, director of global programs for World Learning, said SHERR conducted a survey earlier this year that identified these areas as top ways for higher education institutions to get involved with the resettlement effort.

“We need to connect this initiative as deeply as possible to the educational mission.”

In a breakout session on language learning for career support, the group discussed how to apply for Refugee Career Pathways grants provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Refugee Resettlement. Practitioners also shared ideas on how to help refugees find bridge funding. A refugee might qualify for a federal Pell Grant to pay for college courses, only to learn that it conflicts with other funding stipulations. Case managers for refugee families noted that when this happens, families are often forced to pay for living expenses over classes, slowing their career progression.

Directors from several community colleges stressed they can be great resources, providing affordable options, as well as adult educational and vocational pathways. Avigail Ziv, vice president of programs for Upwardly Global, which provides career coaching, resume writing, and interview practice for refugees who need help reestablishing their professions, said her group wants to share their model with community colleges.

Participants also discussed the need for English language learning that applies to specific careers and job certifications. That can be complex for colleges and universities said Hannah Bonifacius, director of national educational services with the refugee resettlement agency World Relief.

“To sell the idea of partnering on English language learning and career pathways to universities, resettlement agencies must go to them with sources of funding and the messaging that the agencies will be handling the case management of the refugees.”

In a session focused on campus housing for refugees, ElBonita Elliott, a case manager in the UMD Dean of Students office, said the university housed 35 refugees on campus for a year.

To ensure safety and privacy, the campus addressed factors such as drafting fire drill instructions in different languages, removing photos from IDs, designating one emergency contact, and ensuring campus security was aware of cultural norms.

Responding to questions about the legality of allowing non-students and minors on campus, several in the room said it can be complicated but is doable since often there are childcare facilities on campuses or married students with families that involve similar legal parameters.

Participants from Guilford College, Washington State University, Oklahoma State University, and Old Dominion University shared other examples of housing refugees. All noted that the biggest hurdle was money.

The resettlement agency International Rescue Committee provided stipends for the families housed on UMD’s campus, but the university absorbed the rest of the costs. Washington State University used state funds coupled with alternative funding that its president secured. Others suggested tapping individual donors to help.

In a panel led by Joel Colony, World Learning vice president for external engagement and advocacy, panelists encouraged alternative solutions to housing outside of dormitories.

“There are endless opportunities,” said Leslie Wilson, associate director of Refugee Housing Solutions. She suggested working with landlord associations to secure off-campus apartments or repurposing facilities for housing that are no longer in use.

At its School for International Training (SIT) campus in Brattleboro, Vermont, World Learning remodeled residence halls by combining multiple dorm rooms to accommodate families and adding full kitchens. Funding came from a variety of foundations and the state.

But the question remained for many: What is the incentive for colleges and universities to take on the challenge of resettling refugees in the face of a sharp decline in enrollment?

Diya Abdo, founder of Every Campus A Refuge and a professor of English at Guilford College, said that when schools support refugee populations, it enriches students, staff, faculty, and programs. She referred to this as a “collateral benefit.”

“There are 4,000 colleges and universities in the U.S. Everyone can do this,” she said. “We need to connect this initiative as deeply as possible to the educational mission.”

Referencing World Learning’s resettlement program on its SIT campus, Jenkins agreed, “We know that it is not only possible for schools to engage effectively with resettlement, but it’s also consistent with the mission of higher education and beneficial to the entire community.”

Wilson thinks a good first step is getting the right stakeholders together.

“SHERR is a big opportunity. SHERR is an accelerant,” she said.