-

What We Do

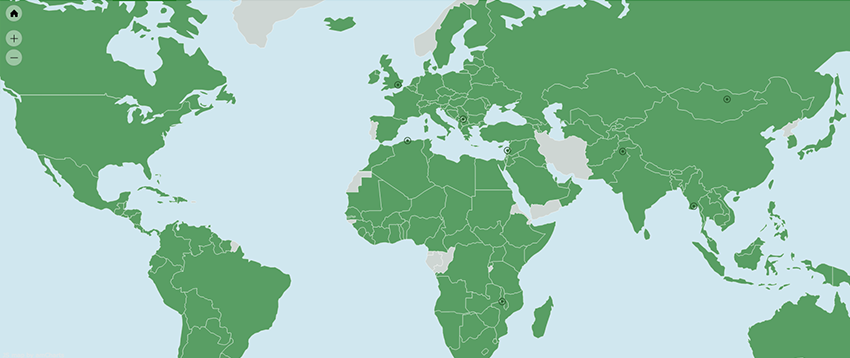

- WHERE WE WORK

-

About Us

Welcome Message from Carol Jenkins

Welcome Message from Carol JenkinsFor more than 90 years, World Learning has equipped individuals and institutions to address the world’s most pressing problems. We believe that, working together with our partners, we can change this world for the better.

On my travels, I’ve had the opportunity to meet with many of those who have joined us in this mission. In Baghdad, we’ve trained more than 2,300 Iraqi youth who are already giving back at home. In London, our partners in the TAAP Initiative strongly believe that we are all responsible to practice inclusion. And in Vermont, our Experiment in International Living and School for International Training participants prove every day that they have the tools and the determination to change the world.

Please join us in our pursuit of a more peaceful and just world.

- Get Involved

Media Center > Story

Building a More Secure World Through International Exchange

June 5, 2018

In an increasingly globalized world, law enforcement officials agree that cross border cooperation is vital to their success, especially those who investigate and prosecute organized, crime trafficking, and money laundering.

“Crime does not know borders,” says Iva Balgac, general police director at the Service for Strategic International Police Cooperation in Croatia.

In April, she was one of 80 law enforcement officials to participate in a three-week International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP) exchange with the focus Towards a More Safe and Secure World: Combating Transnational and Organized Crime.

The program, funded by the U.S. Department of State and organized by World Learning, brought law enforcement professionals from across Europe and the Western Hemisphere to the U.S. to build networks and learn from their American counterparts. They traveled to more than a dozen cities across the country, including Washington, D.C., Tampa, and more, and the trip culminated at the Global Security Conference in New York City.

“For me as a police officer, it’s always good to know a police officer in another country so that you have a direct contact and they can advise you how to solve certain issues,” Balgac says.

While police forces around the world have cooperative agreements allowing them to run a foreign license plate number or set up joint drug trafficking investigations, she says, “if you don’t have a colleague on the other side then [those agreements are] not very useful.”

Building a robust professional network is also critical for those who are responsible for crafting laws governing transnational crime. Bosnia and Herzegovina, for example, looked to U.S. practices and international standards back in the early 2000s when it was reforming its judiciary and police.

Edin Jahic analyzes policy and ensures compliance with international standards as chief of the Section for Fighting Organized Crime and Corruption at the Ministry of Security in the Balkan state. He says his country adopted tools — like plea agreements and a witness protection program — that originated in the U.S. and have proven to be very effective in Bosnia and Herzegovina as well. He hoped to get an even better understanding of U.S. policy by participating in the exchange.

“It’s not enough just to read some provision or international standard explanation,” Jahic says. “You have to understand it in practice, especially if you are not a native English speaker. One word can change the entire work.”

In addition to meetings at federal institutions, Jahic says highlights of the program included meeting analysts from the private sector and universities. He also valued making connections with his fellow European participants.

“I am very fortunate to meet these guys,” he says. “We’ve already made some friendships that are going to last more than these three weeks and, of course, it’s going to be very helpful for my future job.”

Some of the participants already found that the exchange program is helping their work.

Juan Antonio Mateo Ciprian, a public prosecutor for the Attorney General of the Dominican Republic and director of the Department of Counterfeiting Investigations, says the exchange has given him insight into the internal and international cooperation that his U.S. counterparts employ to combat counterfeiting.

He explains that many in the Dominican government — including judges — do not consider forgery a serious crime. He wants to raise consciousness about how forgeries can be used to flout international laws and immigration policies.

Laxity about forgery, Mateo Ciprian says, affects the country’s image abroad and lowers its potential for economic investment. He wants to change that by developing a training course for members of the prosecutor’s office.

“The idea is to eventually create a specialized prosecutor’s office that will help and advise all the various prosecutors in the country,” he says. “The lessons I have learned here will help me a great deal.” He also plans to use the knowledge and connections gained from the exchange program to share knowledge of forgery and contraband with the U.S. Embassy in Santo Domingo.

The Dominican prosecutor says the exchange program was not only professionally enriching but also personally interesting.

“We have seen amazing situations,” Mateo Ciprian says. “We have had visits not only to places such as prisons, but we have also met with homeless people. In general, I have been fascinated to see how crime is prosecuted in this country.”

Written by Amy McKeever, writer/editor at World Learning