-

What We Do

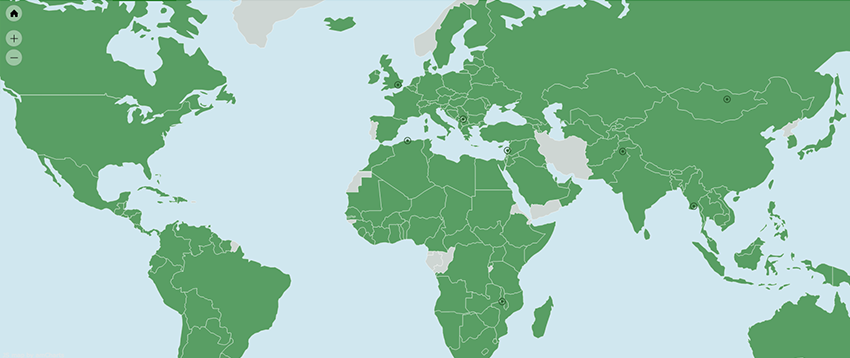

- WHERE WE WORK

-

About Us

Welcome Message from Carol Jenkins

Welcome Message from Carol JenkinsFor more than 90 years, World Learning has equipped individuals and institutions to address the world’s most pressing problems. We believe that, working together with our partners, we can change this world for the better.

On my travels, I’ve had the opportunity to meet with many of those who have joined us in this mission. In Baghdad, we’ve trained more than 2,300 Iraqi youth who are already giving back at home. In London, our partners in the TAAP Initiative strongly believe that we are all responsible to practice inclusion. And in Vermont, our Experiment in International Living and School for International Training participants prove every day that they have the tools and the determination to change the world.

Please join us in our pursuit of a more peaceful and just world.

- Get Involved

Media Center > Story

Meet the Pollaks: How Three Generations of Experimenters Kept their Learning Legacy Alive

April 22, 2022

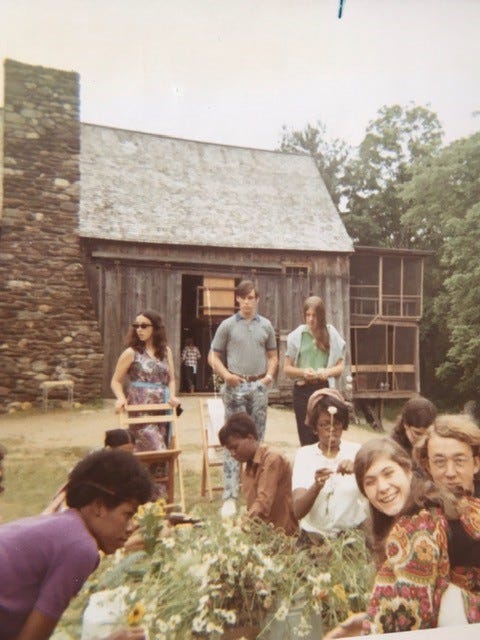

Meet the Pollaks, a family boasting three generations of Experimenters spanning more than 50 years. Their experiences, while each unique, all speak to the power of Experiment founder Dr. Donald Watt’s early vision: People learn to live together by living together.

Jean (deBeer) Pollak, France 1946 and Group Leader France 1947, celebrated her 96th birthday this past fall. The Experiment has remained a strong tradition in her family. Jean’s son, Dick Pollak, Japan 1971, married group member June (Mukoda) Pollak Wallace. Jean’s other son William married Georgia (Brown) Pollak, Sweden 1970. Their two children then went on to be Experimenters as well: Charlie Pollak, Italy 1996, and Sarah (Pollak) Sullivan, France 2000.

Jean (deBeer) Pollak — France, 1946; Group Leader France, 1947

Post WWII, Jean Pollak, then Jean deBeer, crossed the Atlantic Ocean for France as one of the early participants in The Experiment in International Living. She worked with children at a summer camp south of Paris, an experience she remembers fondly all these years later.

Her father was reluctant to let her go overseas but her mother was in favor of her spreading her wings. Europe was rebuilding itself following the war, making for an especially unique experience for many Experimenters.

Jean remembers her mother packing food for her to take on the voyage across the ocean because supplies were still scarce in Europe at the time. She also remembers setting the goal to improve her French.

“By the end of the summer,” she says proudly, “I could speak and understand French because I spoke it daily at the camp.”

In addition to improved language skills, Jean also gained a new sense of freedom and adventure, which fueled her decision to return to France the following summer to serve as a group leader with The Experiment.

After graduating from college, she then worked for The Experiment in upstate New York, recruiting students in the area.

Jean says The Experiment started her lifelong love of travel and passion for other cultures.

Much to her delight, this passion was contagious and ignited a three-generation legacy of Experimenters in the Pollak family over the next 50 years.

June (Mukoda) Pollak Wallace and Dick Pollak — Japan, 1971

June Pollak Wallace, then June Mukoda, left for The Experiment in Japan on her 21st birthday in 1971. On the flight to Oakland for language training, she met Dick Pollak, her soon-to-be husband, for the first time.

June recalls Dick’s mother, Jean, was working for The Experiment at the time and encouraged him to go on the program to get over a bad breakup. Both Dick and June were rising college seniors that summer.

June is of Japanese descent and the youngest of five children, her older sisters having been in an internment camp. It was her family who encouraged her to do The Experiment. One sister had always wished she had done the program, and her mother was excited for June to see her home country. She herself had not returned since coming to the United States.

June’s parents only spoke Japanese, but her own ear for the language was stronger than her speaking. She remembers needing an interpreter when she traveled by bullet train to Hiroshima to meet her extended family. Her grandmother and mother’s siblings lived in a farming community, and no one spoke English. June gained wonderful memories from the trip and souvenirs she has kept to this day.

The trip also fueled her growing thrill for adventure.

“They didn’t speak a speck of English. But you experiment at that age. There’s no fear when you are 21,” June says. “Getting on a plane for the first time and flying halfway around the world was thrilling.”

June also gained a broadened worldview as she learned how another culture lived. But she soon realized the learning curve went both ways.

“The young teenage girls were interested in western dress and hairstyles and a lot of them tried to dye their hair red! They were so curious about us,” June says. “They were very interested in talking to us, especially about going to America.

“For a young woman my age, the experience was enlightening. It opened up the world to me and made me appreciate a multicultural world.”

But the biggest takeaway from her time with The Experiment was her first husband, Dick. They were engaged soon after returning from Japan and married in September 1972. In the coming years, they had a son and daughter before Dick passed away soon after.

“He was so enamored with Japan. Had he lived, we would have gone back,” June says.

Georgia (Brown) Pollak — Sweden, 1970

Georgia Pollak is June’s sister-in-law by marriage. Her husband is William Pollak, Jean’s second son and Dick’s brother. But prior to marrying William, Georgia Brown spent the summer of 1970 in Sweden with The Experiment.

She had just graduated from high school and remembers there was a deep desire in her generation for social and political change at the time.

“The late 1960s was very tumultuous,” says Georgia. “My generation was exploring changes. Changes in the roles of women. Changes in how we looked at society. Changes in how we looked at communal living. I think I thought of Sweden as a very progressive place, and I was curious.”

She first studied Swedish in Putney, VT, before living with her homestay family for eight weeks in Sweden. Time spent with this family provided her with the greatest immersive learning.

“We were really into being anti-Vietnam War. I remember saying to my host family that I wanted to hear more news about what was going on in the United States. But they couldn’t have cared less.

“They didn’t have a revolution, but women had a much more equitable role there, and people were environmentally conscious. They didn’t talk about it; they lived it. They lived in apartments and were very urban and very sophisticated. And then they would go out into the country to their cabins where they had no electricity or water. For myself, I learned there were other ways of living. You move from a myopic view of your own world,” Georgia says.

Both Georgia’s children also went on to be Experimenters right before they applied to college. She recalls her son Charlie learning about the “art of doing nothing” when his homestay family in Italy would spend full evenings simply visiting friends on a street corner.

This story makes Georgia laugh. But she then stresses how important she thinks these experiences were for her children.

“It gave them a really healthy perspective,” she says. Her own memories include a trip back to visit her homestay family after she finished the program. She recalls their generosity, lending her equipment to go skiing.

“They were always terrific,” she says. “I had a truly authentic immersive experience.”

Charlie Pollak — Italy, 1996

Charlie Pollak, Georgia and William’s oldest child, went to Italy with The Experiment the summer before his junior year in high school. Charlie didn’t think of doing the program as part of a family legacy but certainly knew of The Experiment because of his mother and grandmother.

“I knew it was formative for them, and they strongly encouraged me to participate in the program,” he says. But that wasn’t his only motivation.

“I think I was looking for a new experience — a chance to live in another culture and to view my own culture through their eyes.”

One new experience involved a boat trip with his host family. The father dove into the water and returned with a bag of sea urchins. Charlie watched while the family ate the roe on the spot.

“I remember being struck by how laid back they were,” Charlie says of his host family, who lived in Brindisi on the Adriatic coast. “I was coming from a home where I was scheduled top-to-bottom with activities and extracurriculars. My host family kept busy, but it was just much more relaxed.”

As he shared with his mother Georgia, he learned the joy of seemingly doing nothing at all.

“I remember my host family once told me we had plans to meet another family at a certain street corner. We met them there and talked for a few hours. I kept waiting for us all to go somewhere, but we never did. Meeting another family at the corner wasn’t a staging point for a later activity. It was the activity itself. This was a revelation.”

I can’t recommend the program enough. It will broaden your horizons, put you at ease in novel situations, and teach you how to turn strangers into friends.

It was the ordinary times with his host family versus the extraordinary ones that caused another revelation for Charlie.

“They valued friends and meals together, watched MTV, liked to laugh. Seeing another family like this was an important lesson, at a key time in my development, that people all over the world are a lot more similar than they are different.”

Would he recommend doing The Experiment today?

“I can’t recommend the program enough. It will broaden your horizons, put you at ease in novel situations, and teach you how to turn strangers into friends,” Charlie says, highlighting the skills he gained on a personal level.

But he also believes the program has larger implications for our world today.

“Not all the problems of the world are due to fear, prejudice, cultural generalizations, and misunderstanding. But a lot of them are. And there’s no better way to combat those dangerous human impulses, to learn how to individuate rather than condemn whole cultures with prejudice, than by living with people who are different than yourself,” he stresses.

“It’s hard to hate or fear people from another culture when you’ve spent time making a home with them.”

Sarah (Pollak) Sullivan — France, 2000

Sarah Pollak, now Sarah Sullivan, is Charlie’s younger sister. Like her brother, the experiences of her mother and grandmother influenced her decision to do The Experiment. Add to this that Georgia took her on work trips to France when Sarah was just six years old.

“That implanted in me both a love of France and a love of travel. I think it was organic for me to want to have an experience like The Experiment,” she says. “I have really positive memories of the whole time.”

As was the case for all the Pollaks, Sarah’s host family was a large reason for those positive memories.

“I was connected with an incredibly warm host family in the French countryside,” she says, adding the homestay experience cultivates a unique learning opportunity.

“We tend to think ‘what am I going to learn about France.’ What I learned is that I was also bringing a little glimpse of American life to people who don’t know what that looks like. It was enlightening to see it was a two-way street — that I was learning from them, and they were learning from me.”

My experience was hugely immersive from a language perspective. A few years later when I was a junior in college, I went to Paris to study. Having had The Experiment in International Living time a few years prior was a huge leg up in the language area.

Another thing she learned was to be more responsible.

“I had to keep track of my train tickets and schedule. I needed to be organized and get around on my own. It was good preparation for college.”

As was being immersed in the French language since her host family didn’t speak any English.

“My experience was hugely immersive from a language perspective. A few years later when I was a junior in college, I went to Paris to study. Having had The Experiment in International Living time a few years prior was a huge leg up in the language area.”

Overall, the experience expanded her horizons and taught her life skills. She learned how to behave in someone else’s home, not only in a different person’s space but also in a different person’s culture. This made a lasting impression on her.

“In the south of France, people work to live as opposed to living to work. That was the first time I was in an entire community that operated that way. They had a more holistic perspective on their life,” she says.

She also believes The Experiment created a unique bond within the Pollak family.

“We are all people who truly love to travel and experience other cultures.”

Will she encourage her three sons to do The Experiment when older?

“Yes, 100 percent I would encourage my children to go on The Experiment. I want to foster a love of travel and being open to other cultures in my children. It’s really a life skill to stay in someone’s home, speak another language, and live and share their culture,” she says.

Her 8-year-old loves Super Mario, which originated in Japan. This inspired a newfound love of Japanese food and culture.

“Maybe he’ll go to Japan with The Experiment in International Living in 10 years,” Sarah says.

He wouldn’t be the first Pollak to do so, and odds are, he won’t be the last.