-

What We Do

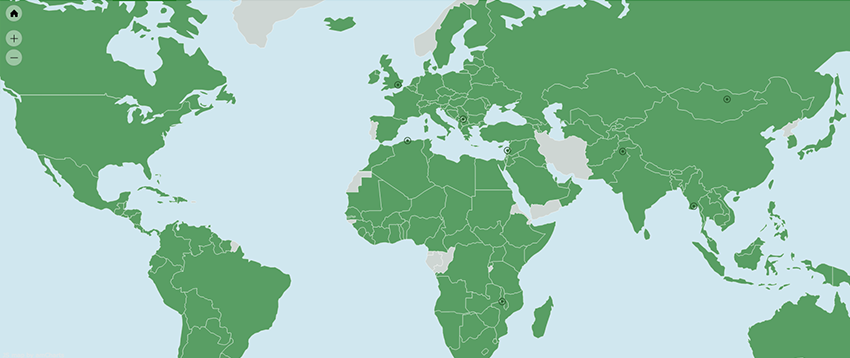

- WHERE WE WORK

-

About Us

Welcome Message from Carol Jenkins

Welcome Message from Carol JenkinsFor more than 90 years, World Learning has equipped individuals and institutions to address the world’s most pressing problems. We believe that, working together with our partners, we can change this world for the better.

On my travels, I’ve had the opportunity to meet with many of those who have joined us in this mission. In Baghdad, we’ve trained more than 2,300 Iraqi youth who are already giving back at home. In London, our partners in the TAAP Initiative strongly believe that we are all responsible to practice inclusion. And in Vermont, our Experiment in International Living and School for International Training participants prove every day that they have the tools and the determination to change the world.

Please join us in our pursuit of a more peaceful and just world.

- Get Involved

Media Center > Story

In Mongolia, Project Citizen Empowers High Schoolers to Change Their Communities

December 11, 2018

In democracies the world over, civic education in schools is seen as a critical rite of passage to citizenship. We prepare young people to get involved in their communities, hold leaders accountable, vote, emerge as leaders themselves, and someday assume the helm of democracy. But this only works when we provide them opportunities to put these democratic norms into practice.

In Mongolia’s capitol of Ulaanbaatar, a team of students at School #29 — the country’s one-and-only school for deaf and hard of hearing students — is showing us what democracy is made of: engagement, dialogue, and an insistence that better things are possible. Working together, these students persuaded their school and the Mongolian government to install a lighting system to alert students to emergencies.

The students were involved in Project Citizen — an interactive methodology used in 60 countries worldwide. The premise for Project Citizen is simple: identify an issue that’s important to your school or community, research the issue, suggest a solution, and carry out a project that will address this issue. In other words, it makes civic engagement real and achievable for students.

The initiative was introduced as part of World Learning’s USAID-funded Leaders Advancing Democracy (LEAD) Mongolia Program, which is cultivating the country’s next generation of democracy advocates. World Learning partnered with Center for Citizenship Education (CCE) — one of country’s oldest NGOs established during Mongolia’s transition to democracy — to introduce Project Citizen at high schools across the country.

Students at School 29 say: nothing about us without us

School 29 is one of 70 schools that participated in Project Citizen this past year.

Tuul Batsuren, a history teacher at School 29 who introduced the initiative, says these skills are especially important for her students because the deaf and hard of community is rarely given a voice in Mongolia. Deaf students are not integrated into Mongolia’s general education scheme and struggle to secure the resources they need.

Batsuren, who is deaf and also a LEAD Mongolia fellow, hopes Project Citizen can change all of this and give her students the voice they need to be active citizens and equal contributors.

About 20 students came together to form the Project Citizen team. Their work began with a school-wide survey to determine the top concerns of students at School 29. One of those concerns was the fact that the school and student dormitories used a traditional bell system to alert students to emergencies or the end of class. But students at School 29 can’t hear the bell, forcing teachers to tell students one by one when to attend class, where to go, or if there was an emergency.

About 20 students came together to form the Project Citizen team. Their work began with a school-wide survey to determine the top concerns of students at School 29. One of those concerns was the fact that the school and student dormitories used a traditional bell system to alert students to emergencies or the end of class. But students at School 29 can’t hear the bell, forcing teachers to tell students one by one when to attend class, where to go, or if there was an emergency.

The Project Citizen team quickly went to work to research their rights and the resources they would need to fix the problem. They gained community support and met with government officials and international organizations to demand a change.

Their efforts were rewarded. Tuul and her students convinced the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science and Sports to commit 10 million Mongolian Tughrik (3,880 USD) to fund a new lighting system to replace the bell system. National television stations also featured the students, allowing them to raise awareness among thousands of Mongolians about the barriers faced by students with disabilities.

It has already made a difference.

“We are so happy to have this light signal in our dorm now,” says Nandin-Erdene, a ninth grader at School 29 who has lived in the dormitories for eight years and participated in Project Citizen. “Everything became much easier for us.”

If we want to change the world, start with high schoolers

Mongolia, as one of the youngest countries in the world, with young people ages 14 to 34 comprising 35 percent of the population, is an especially important place to teach youth about civic engagement. Faced with rising unemployment, corruption and fast-growing discontent with their country’s political climate, Mongolia’s young people are increasingly less optimistic about democracy and less likely to engage in civic or community work to combat these challenges.

For Dr. Narangerel Rinchin — executive director of CCE and a long-standing democracy advocate — the remedy to this is placing the practices of civic engagement directly into the hands of those young people. “If we want to make a positive change in Mongolia, we start with the young people,” she says.

She argues that the most effective way to compel younger people into civic life is to not simply teach civic responsibility but give them to space to act on it. Allowing students to carry out civic action projects based around their own interests offers those young people an opportunity to understand the democracy in which they live — and instills confidence that democracy works. It also provides a constructive approach to understanding the much more complex issues they hear about every day in the news.

This is exactly what Project Citizen achieves.

Rinchin, who has been involved in Mongolian civic life for three decades since the country’s peaceful transition from authoritarian rule to democracy, first introduced Project Citizen at 25 schools in Ulaanbaatar in 1997. Under the LEAD program in 2018, Project Citizen involved 70 schools from 11 different provinces, and will involve up to 100 schools this upcoming year with support from USAID.

Rinchin, who has been involved in Mongolian civic life for three decades since the country’s peaceful transition from authoritarian rule to democracy, first introduced Project Citizen at 25 schools in Ulaanbaatar in 1997. Under the LEAD program in 2018, Project Citizen involved 70 schools from 11 different provinces, and will involve up to 100 schools this upcoming year with support from USAID.

“Project Citizen is a program which adds to students’ knowledge, enhances their skills, and deepens their understanding of how ‘the people’ — all of us — can work together to make our communities better,” Rinchin says. “For young people to carry forward the traditions of democracy, teaching civic education at all levels of primary and second education is vitally important.”

Democracy is more than a set of ideals, it’s about action

Were it not for Project Citizen, School #29 would still have in place a bell system that was at best impractical and, at worst, dangerous. Now, though, students feel empowered to create a positive change in their school and community.

“I am so proud to see that the students learned how to identify a problem and how to act on it after being part of Project Citizen,” Batsuren says, adding that the experience was about so much more than building practical project skills. For Batsuren, it was about allowing the students to see first-hand how they can take charge in their community and make a difference.

Sarantuya, the principal of School #29, says she has seen a change in the students. “Ever since [they participated in Project Citizen], the students have become more vocal, active and empowered to do more,” she says.

Their work has received national recognition. The team won second place in the Project Citizen National Competition in April among the 12 teams that qualified. At the competition, President of Mongolia Kh.Battulga praised initiatives such as this one. “The main purpose of this project is for students to bring up issues and challenges they face at their schools and in their communities through extensive research, develop plans based on relevant laws and regulations, and then propose it to decision-makers to solve it together,” he said. “This is what we want to see happen.”

The project also taught students at School #29 that democracy works — especially when you get involved in civic life. As one participant, Nandin-Erdene, says, “We were so happy that our idea could became reality.”

Watch Project Citizen in action at School 29 in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia:

LEAD Mongolia is a World Learning program funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), which is working with some of Mongolia’s best and brightest emerging democracy advocates. World Learning and CCE partnered under the LEAD Mongolia activity beginning in late 2016 and will continue to offer Project Citizen through 2021 thanks to the support of USAID. CCE first introduced the methodology in 1997 in collaboration with the California Center for Civic Education which developed Project Citizen to promote competent and responsible participation in local and state government. It was funded by the U.S. Department of Education.