-

What We Do

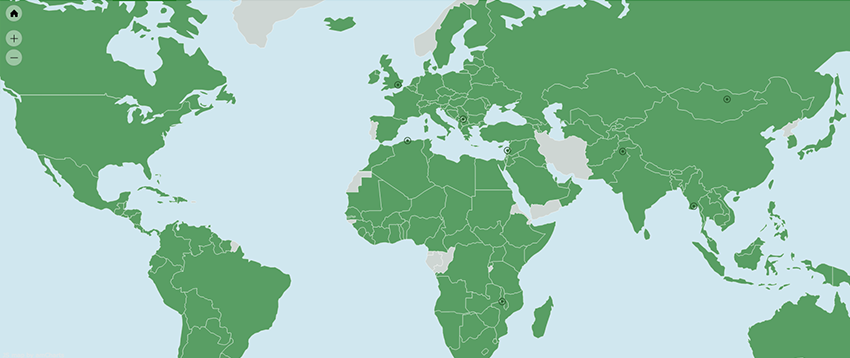

- WHERE WE WORK

-

About Us

Welcome Message from Carol Jenkins

Welcome Message from Carol JenkinsFor more than 90 years, World Learning has equipped individuals and institutions to address the world’s most pressing problems. We believe that, working together with our partners, we can change this world for the better.

On my travels, I’ve had the opportunity to meet with many of those who have joined us in this mission. In Baghdad, we’ve trained more than 2,300 Iraqi youth who are already giving back at home. In London, our partners in the TAAP Initiative strongly believe that we are all responsible to practice inclusion. And in Vermont, our Experiment in International Living and School for International Training participants prove every day that they have the tools and the determination to change the world.

Please join us in our pursuit of a more peaceful and just world.

- Get Involved

Media Center > Story

Expanding Disability Services in Mongolia

March 20, 2017

As part of a series on the Leaders Advancing Democracy Mongolia (LEAD Mongolia) program, World Learning sat down with program participants to learn more about who they are, what they learned from LEAD Mongolia and how they plan to use their experience back home.

LEAD Mongolia is a two year initiative run by World Learning with funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), which aims to bring together aspiring leaders from Mongolia to the United States to learn about democracy, and how they can work together to tackle Mongolia’s most pressing issues, including corruption, poverty, discrimination, urbanization and the environment.

For people with disabilities in Mongolia, there are many obstacles to overcome. Nemkekhbayar Batnasan, a deaf professional living in the capital Ulaanbaatar, says there’s a common misperception that people born with disabilities are being punished for their sins in a past life, which leads to discrimination, and a lack of awareness and information about their needs.

Batnasan, an information officer for the Mongolian National Federation of the Deaf, says there are not enough sign language interpreters in the country, and there are very few programs that offer closed captioning, despite a new law that requires public TV channels to do so.

“Interpreters or written publications make information much more accessible for the deaf,” he says. “However, Mongolian National Broadcasting is the only station that has sign language interpreters, and that’s only during their 40-minute news. That means there’s 68 other TV channels that don’t have subtitles for their programs.”

The opportunities to learn sign language are limited, he says, noting that state universities don’t offer training for interpreters, so the only way to learn is by attending classes at the Mongolian Association of Sign Language Interpreters.

Education for the deaf is also inadequate, Batnasan says, especially in the rural communities, where life can be much harder. He says the majority of students drop out of school. To change that trend, Batnasan says he would like to see sign language used more in public, and wants to make Video Relay Services (VRS) available across the country. VRS is a form of telecommunication available in many developed countries that enables people who are deaf or hard of hearing to communicate through video instead of text.

Batnasan thinks VRS can help in myriad ways, including in emergencies. “Today emergency contact centers [police, medical, fire] only receive voice calls and deaf people cannot call emergency services. If video relaying services are introduced to emergency call centers there would be a huge possibility to connect all district-level agencies such as district hospitals, police, and social service centers.”

Batnasan spent three weeks in the United States as part of the LEAD Mongolia program, run by World Learning and funded by USAID. He says his time in the U.S. allowed him to see how open and inclusive the country is toward people with disabilities.

Batnasan spent three weeks in the United States as part of the LEAD Mongolia program, run by World Learning and funded by USAID. He says his time in the U.S. allowed him to see how open and inclusive the country is toward people with disabilities.

During a visit to Capitol Hill, he had the opportunity to meet with lawmakers and an association for the deaf, which he said deeply impacted him. “I was so proud to see that those people have knowledge, skills and responsibility.”

A team of sign language interpreters worked with Batnasan during the three-week U.S. exchange program in Washington, D.C. and at the University of Virginia. “The sign language interpreters assigned to me were extremely helpful,” he said. “I realized that we need to improve our sign language and deaf children’s education. We should invite experienced volunteers and experts from foreign countries and collaborate with them, and learn from them to improve ourselves.”

Valery Nadjibe, an associate program officer at World Learning, says a Mongolian interpreter was initially going to join, but he had to back out at the last minute due to visa issues. “We searched and searched and we could not find anyone in the U.S. that knew Mongolian Sign Language. So with the help of World Learning program associate, Rebecca Berman, who is also deaf, we managed to get four interpreters.”

Two teams of two interpreters, e with a hearing ASL interpreter and a Certified Deaf Interpreter (CDI), interpreted for Batnasan taking breaks every 20 minutes. With each team, the hearing interpreter signed American Sign Language to the Certified Deaf interpreter, who interpreted in International Sign. Before the program started, the interpreters skyped with Batnasan to get to know him. “They met him at the airport, and were there from that moment on, working with him and supporting him every step of the way,” Nadjibe says.

“World Learning’s mission is to be inclusive for everyone,” Berman says, adding that it’s important to make sure the needs of all participants are met during the planning process. “For this particular program, we helped connect the LEAD organizers with interpreting agencies and we connected them with the DC Deaf Community resources in order to make sure this program was 100% accessible.”

“World Learning’s mission is to be inclusive for everyone,” Berman says, adding that it’s important to make sure the needs of all participants are met during the planning process. “For this particular program, we helped connect the LEAD organizers with interpreting agencies and we connected them with the DC Deaf Community resources in order to make sure this program was 100% accessible.”

Batnasan was very impressed with the support he received and recommends the LEAD program to people of all abilities. “I have learned many new things and heard interesting stories about democracy and freedom with the help of the sign language interpreters provided by World Learning. I think if deaf youths participate in this program, they will be equipped to implement projects and work with other young people, and they will have the support to do so.”