-

What We Do

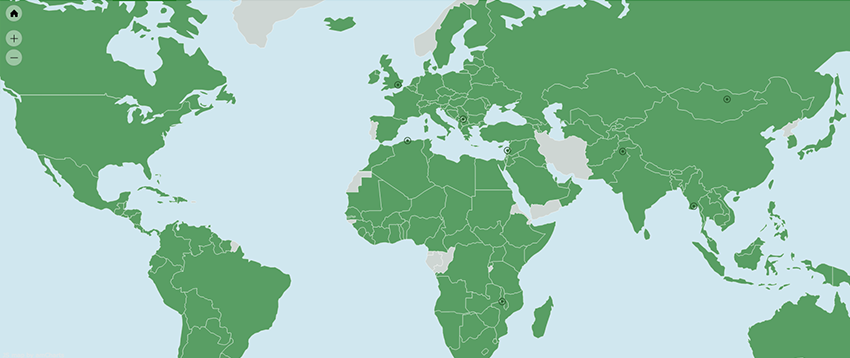

- WHERE WE WORK

-

About Us

Welcome Message from Carol Jenkins

Welcome Message from Carol JenkinsFor more than 90 years, World Learning has equipped individuals and institutions to address the world’s most pressing problems. We believe that, working together with our partners, we can change this world for the better.

On my travels, I’ve had the opportunity to meet with many of those who have joined us in this mission. In Baghdad, we’ve trained more than 2,300 Iraqi youth who are already giving back at home. In London, our partners in the TAAP Initiative strongly believe that we are all responsible to practice inclusion. And in Vermont, our Experiment in International Living and School for International Training participants prove every day that they have the tools and the determination to change the world.

Please join us in our pursuit of a more peaceful and just world.

- Get Involved

Media Center > Press Room > Speech

Women, Peace and Security: More than Victims

Remarks Type: Remarks as Prepared

Speaker: Donald Steinberg, Special Advisor to World Learning

Speech Date: October 18, 2017

Speech Location: Washington, DC

President Trump signed into law on October 6 a remarkable piece of legislation: the Women, Peace and Security Act of 2017. Many years in the making, this law not only highlights the tragic impact of war around the world on women in particular, but also stresses that women are far more than victims. It is based on a simple fact: the meaningful participation of women in peace processes, political systems, and democratic transitions makes for more stable and resilient societies, yields more sustainable agreements, and helps silence the guns of war.

The Act requires the Administration to develop a broad national strategy with specific implementation plans for the Defense Department, State Department, Department of Homeland Security and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to support women’s roles in conflict prevention, peace processes, and post-conflict reconstruction.

Equally remarkable, the legislation was adopted unanimously by both houses of Congress, and its Senate sponsors and co-sponsors ranged from Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH) and Chris Coons (D-DE) to Marco Rubio (R-FL) and Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV), while House sponsors and co-sponsors ranged from Kristi Noem (R-SD) and Ed Royce (R-CA) to Jan Schakowsky (D-IL) and Eliot Engel (D-NY).

This legislation is long overdue. As an American diplomat engaged in peace processes for nearly four decades from Angola to Haiti, from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe, I came to see that the single most important factor to whether a peace agreement could be signed and implemented was the engagement of civil society and marginalized groups at the peace table and in post-conflict reconstruction decision making.

In particular, women bring to the table ground truth, moral authority, longer-term vision and key negotiating skills – such that recent studies have shown that peace processes that included a critical mass of women are far more likely to create long-term peace than those that do not. Women often bring a focus on the root causes of conflict – including poor health, education, sexual violence, and racial and ethnic divisions. They regularly demand the return of rule of law and accountability, recognizing that blanket amnesties too often mean that men with guns forgive the crimes of other men with guns.

The Act builds on important progress under the Obama Administration, including the adoption in 2011 of the National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security. That same year, I had the honor as USAID deputy administrator to announce our first program to provide women peacemakers around the world with stipends, training, and personal security – recognizing that women are often subjected to threats and even physical violence when they dare to step forward as peace advocates and negotiators.

The bipartisan Women, Peace and Security Act of 2017 is a good next step in this process, but it is largely a skeleton on which the Administration and civil society activists must build. Too often, the law includes “should”, “may” and “senses of Congress” when it should be a directive. In fact, the only firm requirements are for the Administration to develop a strategy within a year, report on the implementation of that strategy the next year, and ensure that personnel at State and USAID are trained in these issues. Further, the Act neither authorizes nor appropriates any budgets to achieve its goals.

The American people, Congress, and members of the Administration must insist that the full U.S. foreign policy and defense establishment engage in serious planning, and adopt time-bound, measurable goals to expand women’s meaningful roles in peacemaking efforts — from Syria to Sudan, from Myanmar to Colombia – backed by ample financial and human resources.

One first step would be for the Trump Administration to announce that we will refuse to support any United Nations or regional peace effort that does not include at least 30 percent women participation. After all, why should we invest our funds in processes that we know are likely to fail?

Can the United States afford to focus on women’s engagement at this time of historic international insecurity?

The answer lies in recognizing that countries wracked with conflict and instability are more likely to traffic in drugs, people and weapons; to harbor terrorists and pirates; to transmit pandemic diseases; to generate large numbers of refugees crossing borders and oceans; and to require American boots on the ground.

Since we know that women’s engagement is key to ending conflict and instability, the more relevant question is: Can we afford not to?

Donald Steinberg, special adviser to World Learning, served as USAID Deputy Administrator from 2010-13, the President’s Special Haiti Coordinator from 1999-2001, and U.S. Ambassador to the Republic of Angola from 1995-98.