-

What We Do

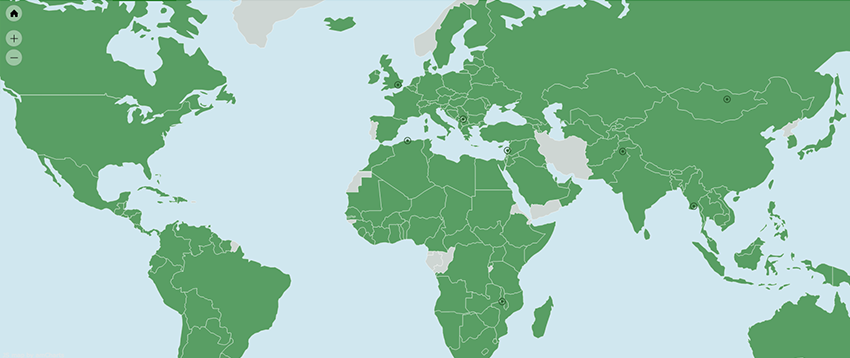

- WHERE WE WORK

-

About Us

Welcome Message from Carol Jenkins

Welcome Message from Carol JenkinsFor more than 90 years, World Learning has equipped individuals and institutions to address the world’s most pressing problems. We believe that, working together with our partners, we can change this world for the better.

On my travels, I’ve had the opportunity to meet with many of those who have joined us in this mission. In Baghdad, we’ve trained more than 2,300 Iraqi youth who are already giving back at home. In London, our partners in the TAAP Initiative strongly believe that we are all responsible to practice inclusion. And in Vermont, our Experiment in International Living and School for International Training participants prove every day that they have the tools and the determination to change the world.

Please join us in our pursuit of a more peaceful and just world.

- Get Involved

Media Center > Press Room > Speech

Connecting the Dots between Gender-Based Violence and Our Common Security

Remarks Type: Remarks as Prepared

Speaker: Donald Steinberg, World Learning CEO

Speech Date: February 13, 2015

Speech Location: Washington, DC

Honored Guests:

I’m honored to serve on this panel to discuss the broader implications of the epidemic we are now facing in gender-based violence. Judith Bass from John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Widney Brown of Physicians for Human Rights, and Henriette Umulisa of the Rwandan Ministry of Gender and Family have done a tremendous job in spelling out the human costs of this epidemic in the Great Lakes region of east Africa, as well as a number of interventions that provide promising models for preventing and responding to such violence. It is my task to place this phenomenon into its global context.

The world is currently responding to the Ebola epidemic in West Africa, a tragedy that has taken the lives of some 9,000 people. While we know that the response was sadly belated, it has been more and more robust as weeks and months go by, involving the contributions of many countries and the investment of substantial amounts of money and manpower from around the world. By contrast, the epidemic of gender-based violence, which certainly impacts hundreds of times as many people as Ebola, has drawn a modest global response. Why?

Connecting the Dots

Let’s start by taking a close look into the mirror. As advocates for this agenda, I believe that we have failed to make the connection between gender-based violence and its broader effects, which in fact impact all of us in every country around the world.

We have failed—so to speak—to connect the dots for our compatriots, such that they now view each act of gender-based violence as an individual tragedy rather than as an element of a threatening global phenomenon. So let me try to suggest an approach that can mobilize greater international engagement.

We should begin by looking at the nature of societies in which gender-based violence is rampant.

First, these societies are marked by the failure of rule of law, since rape, domestic violence, and sexual abuse are not just heinous acts, but actual crimes that are not being investigated and prosecuted. These societies are thus marked by the failure of policing and security systems, especially since the perpetrators are often government forces themselves. These countries are awash in small arms and light weapons, such that violence has become “normalized” and human interaction too frequently takes place at the end of a gun barrel. There is a lack of accountability, not only for perpetrators, but for those in positions of authority, who often either command or condone the violence.

In these societies, civil society groups that should serve as a brake on this violence—institutions of women, lawyers, religious figures and the like—are usually circumscribed, persecuted and powerless to effect change. Such societies also fail to prioritize human security and the well-being of marginalized populations—people with disabilities, the LGBT community, indigenous populations, and ethnic and religious minorities—who are particularly vulnerable to gender-based violence. The percentage of women with disabilities who are victimized when social order breaks down is truly shocking.

And these societies are characterized by governments and non-state actors that are willing to flout international conventions, UN Security Council resolutions, domestic laws, and other norms of acceptable international behavior.

So, in summary, these societies are marked by lack of rule of law, renegade security forces, no accountability, too many weapons, weak civil society, normalization of violence, and the willingness to disobey international and domestic laws, proliferation of small arms. That’s a good description of what we used to call, “failed” or “failing” states—and what we now call, ”weak and fragile states.”

Our Common Stake in Women’s Empowerment

Now let’s connect the next dot. Why should we care about weak and fragile states? Certainly, we have moral and human interests in protecting people within these countries from abuses.

But we also need to remember that crises do not stay put and their effects do not respect borders. I am just returning from a visit to Lebanon, a country of four million people that is being rocked to its foundation by the influx of up to two million Syrian refugees, a phenomenon also impacting Jordan and Turkey.

Let us remind our compatriots that countries where women are empowered and gender rights are respected do not tend to traffic in drugs, people and weapons. They do not send large number of refugees across borders and even oceans. They do not harbor pirates. They do not provide open areas for terrorist training camps. They do not transmit pandemic disease, and they do not require foreign intervention, either as military forces or peacekeepers.

We have already come a long way in our efforts to build a global consensus around these issues. In the last few years, four advocates for women’s empowerment and gender-equality from West Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia have won the Nobel Peace Prize. Films like Lisa Jackson’s, The Greatest Silence, and Abby Disney’s Pray the Devil Back to Hell, have mobilized large numbers of activists.

The Declaration of Commitment to End Sexual Violence in Conflict has been endorsed by two-thirds of the world’s nations. Margot Wallstrom, Sweden’s new foreign minister and formerly the U.N. Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict, has taken the work of such heroes as Hillary Clinton, Mary Robinson, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf and Graca Machel a step further by launching the world’s first “feminist foreign policy.” Civil society groups, governments, foundations, international institutions, and even the private sector are coming together in innovation public-private partnerships to take exciting initiatives and pilots to scale. Advocates are coming together to demand time-bound measurable goals for eliminating gender-based violence—goals that are backed by ample resources; monitoring, accountability, and enforcement provisions, and robust feed-back loops.

And they are demanding that we listen to the voices of the women most impact by these phenomena and be guided by their wisdom, ground-truth, and knowledge of local conditions and mores under the watch-words, “Nothing about them without them.”

Building the Constituency

And yet we have to acknowledge the need to build our constituency further. I am pleased that we have such a large crowd here today—some 100 people—but I also note that here are only twelve men in the room. Presumably, the men in this forum are at other panels dealing with environmental regulations in situations of fragility, the impact of agricultural public policies on reduction of conflicts, and private sector development in fragile states. Is this because those issues are perceived as “hard” issues of development and security, and gender-based violence is perceived as a “soft” issue?

If so, we have a challenge ahead of us in reminding our male colleagues that there’s nothing soft about ensuring the end of formal conflict does not bring an even more persistent and pernicious form of violence against women.

There’s nothing soft about preventing armed thugs from abusing women in refugee and IDP camps, or ensuing that psychosocial support and medical assistance is available, or banning the impunity and amnesty provisions in peace agreements that allow men with guns forgive other men with guns for crimes committed against women and children, or holding governments and non-state actors alike accountable for their failure to protect and empower women in conflict situations

These are in fact the hardest challenges we face in situations of fragility, conflict and violence, and I’m pleased that the World Bank has brought us together here today to address them. Thank you.