-

What We Do

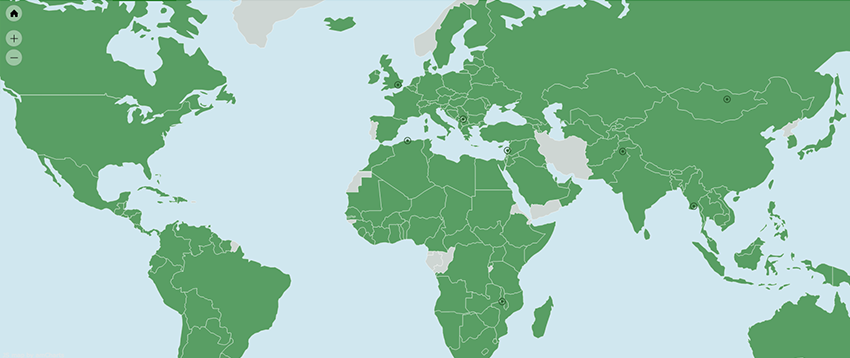

- WHERE WE WORK

-

About Us

Welcome Message from Carol Jenkins

Welcome Message from Carol JenkinsFor more than 90 years, World Learning has equipped individuals and institutions to address the world’s most pressing problems. We believe that, working together with our partners, we can change this world for the better.

On my travels, I’ve had the opportunity to meet with many of those who have joined us in this mission. In Baghdad, we’ve trained more than 2,300 Iraqi youth who are already giving back at home. In London, our partners in the TAAP Initiative strongly believe that we are all responsible to practice inclusion. And in Vermont, our Experiment in International Living and School for International Training participants prove every day that they have the tools and the determination to change the world.

Please join us in our pursuit of a more peaceful and just world.

- Get Involved

Media Center > Story

Meet Bezawit: A WiSci Camper Who is Empowering Women in Ethiopia

March 20, 2019

Bezawit Getachew has been determined to help women in her country cope with injuries from childbirth ever since she first saw the 2007 documentary A Walk to Beautiful.

The film tells the story of five Ethiopian women suffering from obstetric fistulas, small holes between the vagina and rectum or bladder caused by prolonged labor. Fistulas are painful, uncomfortable, and highly stigmatized as they result in incontinence. In some cultures, they are considered a sign that a woman is cursed. In the documentary, all five women are ostracized by their communities and relocate to the capital city Addis Ababa to receive care at a special hospital.

Getachew was moved when she saw the film and realized the hospital was founded by aid workers from Australia. “Those foreigners have done these things for our country,” she says. “As long as I’m here, I have the moral obligation to do something for my own country and make a change.” But while the 17-year-old wanted to help, she didn’t know where to begin, nor did she have the resources to fund a project supporting women with obstetric fistulas.

That has changed. In September, Getachew launched an initiative called She Can, a series of workshops on topics from entrepreneurship to empowerment for women and girls at the Hamlin Fistula Hospital in Addis Ababa. Getachew credits an unforgettable experience at the 2018 Women in Science (WiSci) Girls STEAM Camp with helping her make her project a reality.

A Transformative Summer in STEAM

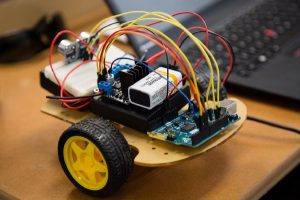

Robots whizzed across the classroom floor at the Namibia University of Science and Technology last summer. The WiSci camp had taken over the university’s campus for nearly two weeks, bringing together about 100 girls from Ethiopia, Kenya, Namibia, eSwatini, and the United States to discover science, technology, engineering, arts and design, and mathematics (STEAM).

Robots whizzed across the classroom floor at the Namibia University of Science and Technology last summer. The WiSci camp had taken over the university’s campus for nearly two weeks, bringing together about 100 girls from Ethiopia, Kenya, Namibia, eSwatini, and the United States to discover science, technology, engineering, arts and design, and mathematics (STEAM).

Implemented by World Learning, the camp is a private-public partnership between the U.S. Department of State’s Secretary’s Office of Global Partnerships, UN Foundation’s Girl Up initiative, Intel Corporation, and Google. Those organizations — and others such as NASA — came to Namibia to teach the girls how to use technology to improve their world and mentor them as they embark on careers in STEAM.

Getachew applied to WiSci last year because she wanted to be part of something real. She shared her culture with fellow campers and learned about their lives in the U.S. and other African countries. She learned how to design apps to serve people with disabilities. And she learned how to dream up, carry out, and fund projects that would serve her community.

Getachew applied to WiSci last year because she wanted to be part of something real. She shared her culture with fellow campers and learned about their lives in the U.S. and other African countries. She learned how to design apps to serve people with disabilities. And she learned how to dream up, carry out, and fund projects that would serve her community.

“WiSci really taught me that we girls must help each other to be greater,” Getachew says. “I have learned more about being a leader, a team player, and how to do these things together.”

Translating Knowledge into Action

Getachew returned home from WiSci ready to use her new skills to accomplish her long-held goal to support and empower women suffering from obstetric fistulas. This time, she had the resources she needed.

Among those resources was a newly expanded network of like-minded girls from her hometown. Understanding the importance of collaboration, Getachew reached out to her fellow WiSci alumnae from Addis Ababa about her idea to host women’s empowerment workshops at the Hamlin Fistula Hospital. Hildana Workija and Medlot Berihun loved the idea and joined her in carrying out the project.

Among those resources was a newly expanded network of like-minded girls from her hometown. Understanding the importance of collaboration, Getachew reached out to her fellow WiSci alumnae from Addis Ababa about her idea to host women’s empowerment workshops at the Hamlin Fistula Hospital. Hildana Workija and Medlot Berihun loved the idea and joined her in carrying out the project.

Now a team, the girls of She Can looked to their experiences at WiSci for inspiration as they developed workshops covering a different theme each week over the course of two months. They borrowed icebreakers and empowerment-building exercises from the daily Girl Up classes, and developed workshops about career and entrepreneurship opportunities based on what they’d learned from the U.S. Department of State and World Learning. And the team set aside time for mentorship, just as they had prized the mentorship of professionals from Google, Intel, NASA, and other organizations.

“I was the one being taught and now I get to be the mentor,” Getachew says. “I wanted to give that experience [from WiSci] to those people who are in the Hamlin Fistula Hospital. We wanted to show them that they can do anything.”

To make all of these plans a reality, though, the She Can team would need funding — and, again, WiSci was there to help. With the support of the Lewy Family Foundation, World Learning offered mini-grants to 12 alumnae from the 2018 WiSci camp to carry out projects in their communities. Getachew, Workija, and Berihun submitted their proposal and won a $1,400 grant to buy T-shirts and personal hygiene care packages for participants, as well as workshop supplies like pens, paper, and snacks. With that, they were ready to get started.

Passing it on

She Can launched at the Hamlin Fistula Hospital in September and, over the course of two months, made great strides in supporting and empowering its residents.

As Getachew had learned from the A Walk to Beautiful documentary, many women with obstetric fistulas have suicidal thoughts and withdraw from their communities and each other. So, the three group leaders from She Can took every opportunity to remind their participants — women and girls ages 14 to 65 — that they deserve all the same rights and opportunities as men. “They may have the capability to do something greater, but society doesn’t tell them that,” Getachew says. “Society has turned their backs on them.”

As Getachew had learned from the A Walk to Beautiful documentary, many women with obstetric fistulas have suicidal thoughts and withdraw from their communities and each other. So, the three group leaders from She Can took every opportunity to remind their participants — women and girls ages 14 to 65 — that they deserve all the same rights and opportunities as men. “They may have the capability to do something greater, but society doesn’t tell them that,” Getachew says. “Society has turned their backs on them.”

The She Can team encouraged participants to get an education or develop their careers so they are able to live independently. They shared resources for online and other learning opportunities, helped women register for identification cards and create bank accounts, and taught them how to develop and pitch their business ideas. They also brought in female mentors to share their experiences in the fields of engineering, banking, the law, and women’s rights advocacy.

It had an impact. While many women were shy at first, they soon began to share their stories with one another. As the She Can team noted in their final project report, participants “started to be more confident, interactive, motivated, and active each day.” The workshops were so well-received that attendance ballooned from 32 to 84 women and girls by the end of the series. “I was amazed and a little inspired,” Getachew says.

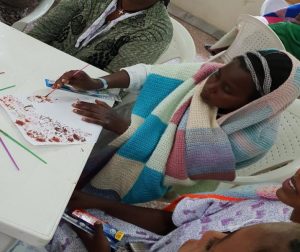

But Getachew found it particularly rewarding to have had the opportunity to meet and inspire a 16-year-old girl named Chaltu. Hailing from the southern region of Ethiopia, Chaltu at first struggled to participate in the workshops as she was the only patient in the hospital who spoke her regional dialect. Getachew and her partners had vowed to make the workshops accessible to everyone, though, so they added visual aids and even a new workshop theme focused on painting and the arts.

But Getachew found it particularly rewarding to have had the opportunity to meet and inspire a 16-year-old girl named Chaltu. Hailing from the southern region of Ethiopia, Chaltu at first struggled to participate in the workshops as she was the only patient in the hospital who spoke her regional dialect. Getachew and her partners had vowed to make the workshops accessible to everyone, though, so they added visual aids and even a new workshop theme focused on painting and the arts.

“It was hard to see her struggle to connect socially with the other patients during our group discussion and we didn’t want her to miss out just because no one really speaks her language,” Getachew wrote in the final report. “But when we introduced painting this whole thing was turned around.” Chaltu discovered a passion for painting. Through a hospital translator, she told the She Can girls that it was her first experience with the arts, which were frowned upon in her community. Inspired, the girls put together a bag full of art paper, a paint brush, and watercolors so that she could continue her artistic journey. “We want her to think that the world also cares about her abilities,” Getachew says.

A Lifelong Commitment to Making a Difference

She Can has made a difference not only in the lives of the participants but for Getachew, too. “I never thought I would be capable of leading such a project,” she says. She now knows that she’ll be able to take on any projects or opportunities that present themselves.

Getachew is also more determined than ever to dedicate her life to uplifting women and girls. Beyond continuing to pursue her passion for STEAM subjects — Getachew loves biochemistry and physics and hopes to become a gynecologist or pediatrician one day — she now plans to pursue humanitarian work at the global level when she graduates from high school. “I want to be a voice for the voiceless,” she says.