-

What We Do

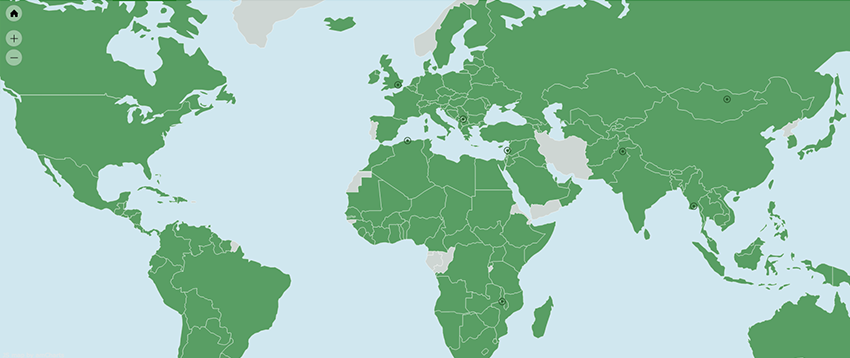

- WHERE WE WORK

-

About Us

Welcome Message from Carol Jenkins

Welcome Message from Carol JenkinsFor more than 90 years, World Learning has equipped individuals and institutions to address the world’s most pressing problems. We believe that, working together with our partners, we can change this world for the better.

On my travels, I’ve had the opportunity to meet with many of those who have joined us in this mission. In Baghdad, we’ve trained more than 2,300 Iraqi youth who are already giving back at home. In London, our partners in the TAAP Initiative strongly believe that we are all responsible to practice inclusion. And in Vermont, our Experiment in International Living and School for International Training participants prove every day that they have the tools and the determination to change the world.

Please join us in our pursuit of a more peaceful and just world.

- Get Involved

Media Center > Story

Ukrainian Journalist Turns to Small-Scale Diplomacy to Enact Big Change

November 1, 2015

“There are no Ukrainians here,” Mykola Vorobiov laments when talking about about the atmosphere in Washington, DC. Now, in a critical time for his country, Vorobiov sees this as a matter of national security, rather than what would otherwise be a casual nuisance.

As the senior editor for Ukraine’s “Euro-patrol” investigative bureau, Vorobiov has reported from his embattled nation long before the start of the unrest in 2013. He was present during the Euromaidan protests, and spent two months in eastern Ukraine covering the frontlines in fall 2014. Russian media portrayed him as a CIA agent and accused him and two friends of organizing the revolution in Kiev.

Vorobiov has been in Washington, D.C., since January on a mission to bolster relations between the United States and Ukraine, which he sees as a critical task to ensure the safety of his own people and the future of his country. “Our embassy is not active enough,” he asserted. “It could have done more for our country.”

“Since I am nearly the only person here from Ukraine,” Vorobiov, said, barely kidding. “I can do diplomacy, I can do policy, I can do journalism. I am trying to do as much as I can.”

In the past few months, Vorobiov has appeared on C-SPAN and in conference rooms across the capital to brief whomever will listen – at George Washington University, the Heritage Foundation, World Learning – on on-the-ground developments in Ukraine he claims the western media are failing to report.

The so-called Minsk-II ceasefire agreement – which was signed on February 12 in Belarus in an attempt to cease hostilities in eastern Ukraine – has proven to be a failure, as separatist rebels forced Ukrainian troops into retreat from the city of Debaltseve shortly after it was meant to take effect. At present, the United Nations estimates that more than 5,000 Ukrainian civilians have been killed since April 2014.

On Tuesday, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry blamed Russia for “persisting in their misrepresentations – lies – whatever you want to call them” when addressing the country’s involvement in Ukraine.

The 28-year-old journalist, who goes by “Nick” when here, is not shy about his admiration for the United States: within an hour-long conversation he calls it, “a perfect country,” “the best country,” “a holy land,” and reckons, according to his experience, “the majority of people who hold anti-American sentiments have never been to America.”

“I don’t know any better place,” he said.

But there is also a sense of urgency, even desperation, to his adulation. For Vorobiov, the survival of Ukraine depends on the imminent decisions of American lawmakers. If they fail to act soon, he said, “Russian tanks will be in Kiev.”

This year, along with an American and Ukrainian activist, Vorobiov founded the Center for Eastern European Perspectives as an answer to what he sees as a dangerous gap in understanding between the U.S. and Eastern Europe – which has led to the ineffective diplomatic efforts he is almost single-handedly trying to rectify. Vorobiov considers the Iron Curtain to be still very much in place, and he believes the Russians are using it to their advantage.

“We founded the Center to play the role of mediator between the United States and the eastern European region,” he said. “There is officially only one Ukrainian journalist working in the United States. You can imagine how important something like this is, especially with the presence of the Russian media – or should I say army – which attacks on all different fronts.”

The Center for Eastern European Perspectives is part think-tank, part facilitator of people-to-people diplomacy. Vorobiov said he modeled it after his first experience in the United States, which was as a participant of the U.S. Department of State’s International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP) in August 2013.

The IVLP Program, which was conducted and designed by World Learning, an international non-profit focusing on education, development, and exchange programs, took four other mid-career Ukrainian journalists across the United States over a span of three weeks for trainings and cultural events. Vorobiov credits the experience as a life-changing opportunity that made him realize the importance of small-scale diplomacy, especially between the U.S. and Eastern Europe.

“This is the best way to educate groups, journalists, scholars, or politicians – bring them here, show them around, give them time to spend freely, informally,” he said. “We still have prejudices – even my generation has them about the U.S., they are filled with conspiracies. Soviet judgments didn’t disappear with the Soviet Union. This is what you do if you want to destroy a myth.”

Vorobiov is slated to return to Ukraine in March, and is actively trying to convince scholars, congressmen, staffers – anyone with clout – to come back with him.

“They need to see things with their own eyes,” he said. “Talk to people, visit military hospitals, see wounded soldiers and in what condition they are treated – talk to volunteers who literally feed the army. See the way they defend their country.”

“The United States is our main ally in this conflict,” Vorobiov said. “Their decisions are what will determine if our country will survive.”