-

What We Do

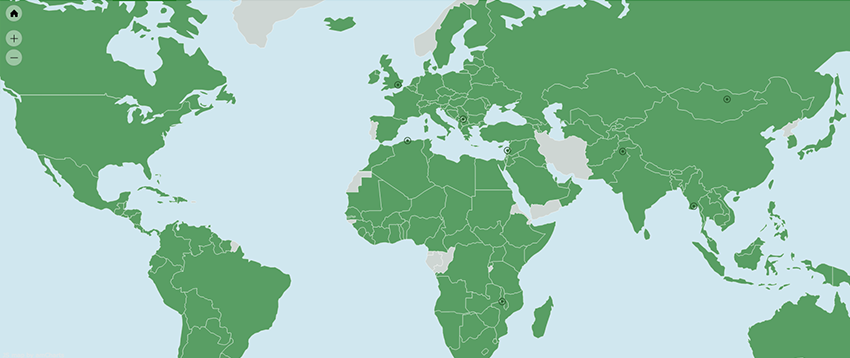

- WHERE WE WORK

-

About Us

Welcome Message from Carol Jenkins

Welcome Message from Carol JenkinsFor more than 90 years, World Learning has equipped individuals and institutions to address the world’s most pressing problems. We believe that, working together with our partners, we can change this world for the better.

On my travels, I’ve had the opportunity to meet with many of those who have joined us in this mission. In Baghdad, we’ve trained more than 2,300 Iraqi youth who are already giving back at home. In London, our partners in the TAAP Initiative strongly believe that we are all responsible to practice inclusion. And in Vermont, our Experiment in International Living and School for International Training participants prove every day that they have the tools and the determination to change the world.

Please join us in our pursuit of a more peaceful and just world.

- Get Involved

Media Center > Press Room > Speech

Trading Places: A Partner’s Perspective USAID Forward and Global Development

Remarks Type: Remarks as Prepared

Speaker: Donald Steinberg, World Learning CEO

Speech Date: May 9, 2016

Speech Location: Washington, DC

Honored guests:

I am pleased to have this opportunity to address the distinguished alumni of USAID. When my good friend and World Learning trustee Tom Fox raised this idea with me, it seemed only natural that I use this opportunity to reflect on my experience as deputy administrator at USAID under the first term of the Obama administration and on my subsequent contact with USAID as CEO of World Learning, a non-governmental organization committed to capacity building and youth empowerment through exchange, education and development. I originally entitled this presentation “Both Sides Now” and to paraphrase Joni Mitchell: “I’ve looked at AID from both sides now, from in and out, and still somehow, it’s AID’s illusions I recall. I really don’t know AID at all.”

USAID on the Ropes

Toward the end of his confirmation process as USAID administrator, Rajiv Shah asked me to meet with him to discuss the possibility of my serving as his deputy. The meeting was on a weekend, and we had unlimited time. It was one of the strangest job interviews I’ve ever done. We didn’t talk about my qualifications, how we might divide the front office responsibilities, or how we would mesh together. Instead, we shared our impressions of the state of USAID, and what was needed to ensure that the agency was the world’s premier development donor.

We started by saluting the talented career civil and Foreign Service officers who kept the agency moving ahead in good times and bad. In particular, we acknowledged the efforts of Alonzo Fulgham and Jim Kunder as acting administrator and deputy, as well as former administrator Henrietta Fore for starting to address some of the problems we saw. In truth, we shared a remarkably similar assessment of USAID, which we both described as “evisceration.”

Over the previous decade and a half, USAID’s work force declined by 40 percent at the same time that assistance budgets were rising rapidly, especially after 9/11. The resulting increase in workload drew too many officers away from being true development partners to contractors and grantees, and focused their attention on getting money out the door. Similarly, policy planning and budget functions were transferred to the State Department F bureau. State Department-appointed assistance coordinators were designated for increasing numbers of countries, like Afghanistan, Pakistan, Egypt, Sudan, and Iraq, such that AID mission directors often were not the lead voice on development assistance at their diplomatic posts.

Perhaps the clearest “no confidence vote” came in the form of the creation of new foreign assistance programs outside of USAID’s control. The two most prominent examples were the Millennium Challenge Corporation and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Both had missions that were closely aligned with USAID, but were created with independent structures and boards. Even OPIC, which was formed essentially as a U.S. government insurance agency, began defining itself as the development finance branch of the USG. The Feed the Future initiative was divided among several agencies. CDC, State, HHS and others competed for health relationships. This is not to mention the Defense Department’s pre-eminent role in conflict situations in Afghanistan and Iraq. Indeed, 26 U.S. government agencies could claim mandates for working in development assistance arenas abroad. 26 different agencies defined roles. It was hard to say that USAID was even first among equals.

The State and Defense Department often usurped USAID’s traditional role in humanitarian relief situations. The Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance and the broader DCHA bureau were matched against PRM at State in particular. Other frictions emerged. State had established the de facto principle that whenever the root cause and ramifications of a humanitarian situation went beyond strictly natural disasters, State took the lead. And of course it perceived that every situation fell into that category.

Finally, USAID officials were largely excluded from inter-agency meeting at the National Security Council, including DCs and PCs, even when they were dealing with issues related to AID’s humanitarian, recovery, and development assistance.

Planning a Transformation

Raj walked me through some ideas for what he called, “USAID Forward.” We agreed that the key to addressing these concerns was the successful conclusion of the Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review (QDDR) that Secretary Clinton had launched.

I was chosen for Deputy Administrator soon thereafter. One reason I was picked was that I knew the State Department and could smooth the process of working together, especially in the QDDR negotiations. I spent 29 years in the system, serving as Ambassador, director of Joint Policy Council, deputy director of policy planning, deputy assistant secretary for PRM, and in six embassies.

My potential role was misunderstood by some. My friend Tony Lake, for example, called me to say that he was being asked about my nomination. Before he endorsed me, he wanted to know: was I going to seek to empower USAID or was I coming to deliver the coup de grace? Assured that it was the former, he became one of my strongest advocates.

Flash forward three years to summer of 2013, when I was preparing to leave USAID. The QDDR was complete and State and USAID had started to implement it. With the help and understanding of Secretary Clinton, Counsellor Cheryl Mils, and Policy Planning director Anne Marie Slaughter, it was a success. No — it wasn’t a declaration of independence for USAID, as some had sought, but neither was it a death sentence. It was a recognition that an empowered USAID, working within the context of a foreign policy and national security agenda defined by the President and Secretary of State, could be a vital contributor to our development, diplomacy and security objectives.

I knew it was a success when I briefed a group of Hill staffers who I knew were skeptical of foreign assistance. When I indicated all the ways in which USAID had been empowered, one staffer said he was confused. “The QDDR wasn’t supposed to be a blueprint for USAID’s empowerment,” he said. “It was supposed to be a blueprint for USAID’s elimination.”

USAID Re-Empowered

What were the indications of USAID’s empowerment? First, the agency re-established its Office of Budget and Resource Management and it was mandated to prepare a comprehensive USAID budget proposal to be reviewed and approved by the Secretary and incorporated into the overall assistance budget. The Bureau of Policy, Planning and Learning was created and charged with developing a series of policy documents and with institutionalizing positive changes within our regulations. USAID was authorized to continue with a strategic hiring initiative, begun under Administrator Fore, to bring on 1,100 new officers. To address the hollowing out of the career corps, USAID was permitted to triple the level of mid-level hires to 95 under the Development Leadership Initiative.

The QDDR had clarified that USAID mission directors were the top advisers on development at U.S. diplomatic posts, and restricted the establishment of Foreign Assistance Coordinators to a limited number of special circumstances. It re-asserted USAID’s expanded role in promoting empowerment and protecting women and other marginalized groups, and transferred leadership and accountability for Feed the Future to USAID. Finally, it endorsed the remainder of the USAID Forward reforms.

Not everything was sweetness and light, of course. Struggles remained over leadership in global health, including one U.S. ambassador in Africa who actually divided his country province-by-province between USAID and CDC. Further, we never truly resolved the DCHA/PRM situation, or leadership in crises and humanitarian situations, and the overlap between OTI and the Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations.

And how was USAID using this expanded influence? First, it used its convening authority to draw together partners across governments, international institutions, civil society, and the private sector. It made strategic investments that leveraged other people’s money, including by reducing risk factors. The agency also linked with other U.S. government entities to put together coherent packages of aid, trade and investment promotion under the President’s Partnership for Growth program. Related to this effort was a new emphasis on public-private partnerships, about 1,200 of which had been created.

USAID also applied focus and selectivity, concentrating its efforts with depth and scale on food security under the Feed the Future Initiative, basic literacy, global health, economic growth, and humanitarian response. It also reaffirmed the need for world-class monitoring and evaluation through the adoption of time-bound, measurable goals with feedback loops and accountability provisions, and the incorporation of science and technology into all its efforts. The agency also broadened its efforts in inclusive development, bringing on coordinators charged with mainstreaming and integrating gender, disabilities, youth, indigenous populations, and LGBT issues into all of our programs, and infusing these principles into our agency’s DNA.

To complete the USAID Forward agenda, there was a new emphasis on capacity building and country ownership. This went well beyond the requirement to channel 30 percent of development resources through local systems. Nor did it mean that USAID would risk taxpayers’ dollars by working with potentially corrupt or inefficient entities; instead, it focused on building and working through sustainable country systems in partner countries through implementation and procurement reform.

Eliminating Extreme Poverty: Ambitious and Aspirational

Finally, just before I left, President Obama established a new and ambitious goal. One of the proudest moments in my career came when the President used words I helped draft in his 2013 State of Union address. He said:

“The United States will join with our allies to eradicate extreme poverty in the next two decades: by connecting more people to the global economy; by empowering women; by giving our young and brightest minds new opportunities to serve; by helping communities to feed, power, and educate themselves; by saving the world’s children from preventable deaths; and by realizing the promise of an AIDS-free generation.”

These words are now mirrored in statements by the World Bank, United Nations, and major aid agencies around the world. And they were incorporated into the Sustainable Development Goals just adopted in New York.

A Partner’s View

So how does all of this look from the other side? I have now been with World Learning for almost three years. We are a mid-sized NGO and academic institution committed to empowering a new generation of global leaders and citizens through education, exchange and development programs.

World Learning began in 1932 as the Experiment in International Living, which provides summer abroad programs for high school students. Some 70,000 young people have gotten their first international experience through this program, which includes home stays, community service, language study, and a focus on global issues like climate change, post-conflict recovery, or human rights.

Similarly, we now provide semester study abroad opportunities for college sophomores and juniors. About 2,100 students will travel abroad this year through SIT Study Abroad, going in small groups for experiential programs that are both academically rigorous and personally transformative. Participants learn advanced research skills and can serve in internships with local academic, advocacy, and civil society organizations. Students get full academic credit for these programs, since we are a fully accredited academic institution.

We also operate our own graduate school in Vermont and Washington, D.C. The School for International Training offers master’s degrees in sustainable development, peacebuilding and conflict transformation, international education, TESOL, and cross-cultural management. The program includes a practicum component, where students spend time with an institution of their choice, and report back through a capstone presentation.

Our fourth focus is on In-bound exchange. Working with a number of government and private entities, each year we bring about 120 groups of visitors for intensive programs in the United States. Under USAID’s Forecast mechanism, the State Department’s International Visitors Leadership Program, and other projects, we bring Palestinians and Israelis together, Indians and Pakistanis together, and so on. We are also proud to be launching a virtual exchange between American and Middle East young people under the Chris Stevens Initiative.

One indication of the success of these four programs is that World Learning has been associated with four Nobel Peace laureates. Landmine activist Jody Williams received her master’s from our Graduate Institute; Kenyan women’s rights and environmental advocate Wangari Maathai served on our board; Yemeni journalist and women’s rights defender Tawakkol Karman got her first international experience through one of our exchange visits to the United Sates; and Indian child rights leader Kailish Satyarthi published with our professors.

World Learning in the Development Arena

Perhaps most relevant for this discussion, however, is the fact that we are a capacity-building NGO with about $100 million in 60 projects in dozens of countries worldwide, and that four-fifths of our funding comes from USAID.

For example, we are working with the International Rescue Committee in Pakistan to train 90,000 teachers to build a quality literacy system that is open to girls and that can compete with the madrassas. We are assisting 300 communities in Lebanon that are impacted by Syrian refugees, helping to limit the tension and xenophobic reaction by expanding capacity in local schools and establishing dispute settlement mechanisms. We are establishing experiential STEM education high schools in Egypt, including for adolescent girls, in which they are using digital fabrication laboratories with 3D printers and crowd sourcing capabilities to address Egypt’s most pressing challenges. And we are leading a consortium of U.S. universities helping to reform the higher education system in Kosovo, adapting it to the needs of an independent country with a modern economy.

Predictable, Supportive, and Like-Minded

What has been our experience with USAID as a funder and a partner? Generally very good. The agency has been a predictable funder, generally sensitive to pain points for contractors and grantees. Burdensome regulations are being streamlined and simplified under the 2 CFR 200 process. We also welcome USAID’s transparency and openness to policy dialogue and budget discussions, including in preparing positions the agency will put forward in international meetings and summits. It is also reassuring to know that the decisions on RFA and RFP processes are communicated clearly.

Further, while there may be challenges in timely responses within the NICRA system, the system ensures that the U.S. government is arguably the only official partner in the world that pays its full share of indirect and overhead costs. USAID has also been open to no-cost and cost extensions. Its world-class monitoring and evaluation system meshes well with a growing attention to M&E within our own organization, with time-bound measurable goals, feedback loops, and accountability provisions tied not to inputs or outputs, but outcomes.

Finally, it is clear that USAID and World Learning are part of a global community of practice that share basic priorities: eliminating extreme poverty, building local ownership, empowering previously marginalized populations, creating resiliency, and breaking down the barriers between relief, recovery and development.

Steep Learning Curve on Partnerships

Of course, there are frustrations and unintended consequences associated with USAID policies and practices, and I would like to refer to a few.

In particular, USAID is still learning – as are we all – about how to be a good partner. This is especially important, given that USAID’s website highlights its partnerships with “corporations, faith-based and community organizations, NGOS, researchers, scientists, innovators, USG agencies, and the military.” For NGOs, it is also important to note that our institutions bring to these partnerships not just ground truth, people-to-people relationships, vast experience, and outreach to the American people, but we also generate more financial resources collectively than the entire U.S. government. In recent years, American civil society has provided more than $40 billion in development and humanitarian resources to developing countries; while official development and humanitarian assistance is $35 billion.

NGOs appreciate USAID’s use of its convening authority to bring together diverse partners, but there is a difference between facilitation and dictating terms.. The essence of this challenge comes from a classic Aretha Franklin song: R-E-S-P-E-C-T. For example, contracting and agreement officers who have worked for other more directive U.S. government agencies are struggling to adopt a collaborative approach. And frequently, USAID’s matchmaking efforts result in shotgun weddings among institutions that have very different visions of success.

Partnerships sometimes come at an expensive price for NGOs. The requirement for cost shares in U.S. government awards can be onerous. World Learning has to generate up to $5 million in complementary funding for our projects in Egypt and Lebanon, a level that can strain the fundraising capacity for all but the largest NGOs.

Other concerns include the requirement to highlight USAID’s brand at the expense of our own. I recognize the strategic importance of reminding local citizens that the assistance comes from the U.S. government and people, but implementing organizations need to get public credit for their work in order to stimulate additional charitable giving, not to mention the encouragement that such recognition provides to workers who rarely get adequate financial benefit from their courageous service in difficult environments.

NGOs too often find ourselves caught in the middle. USAID often requires us to take actions that are unacceptable to local governments, businesses, and civil society. If the full weight and power of the U.S. government has failed to gain support from local entities, it is hard to imagine how an NGO like World Learning can do so. NGOs are also caught in the middle between Washington and overseas missions. Decentralization of power to the field – empowerment of AID mission directors and agreement/contract officers – was an effective survival mechanism when USAID in Washington was under attack. But allowing mission directors to interpret Washington policy mandates according to their own dictates is a prescription for conflict and confusion in working with global NGOs.

Notwithstanding reasonable support for indirect and overhead costs, USAID often fails to put its money where its priorities are. Too many RFA and RFPs fail to provide adequate resources for high USAID priorities, including diversity, M/E, local empowerment, communications and science and technology. For NGOs, these objectives become unfunded mandates.

Finally, even like-minded institutions have differing priorities, especially in terms of working in high-risk security environments. In Pakistan, for example, I was able to persuade the World Learning board and private funders that it was worth taking the security, financial, and reputational risks of working there only by stressing the importance of girls’ education and empowerment, evoking the image of Malala Yousafzai. It was disappointing when a senior Administration official told my staff, “I want to pay World Learning the ultimate compliment – we consider you a key strategic partner in combatting violent extremism.”

America’s Stake in Global Development

To conclude, it is vital that we avoid these missteps, because the new world of global development requires our closest cooperation. We must ensure that we will continue to seek public support by showing Congress and private donors alike that we know what we’re doing, that we are producing measurable and sustainable results, that we are good stewards of their dollars, and that we are channeling their resources through modern development enterprise. The American people want to support us, because they know that prosperity and human security abroad promotes our national security interests, our national economic interests, and our national values.

It is in our national security interest because stable, prosperous countries are less likely to traffic in arms, drugs, and people; to send off large numbers of refugees across borders and even oceans; to serve as hosts for terrorist training camps and pirates; to incubate and transmit pandemic diseases; and to need American forces on the ground.

Development is in our economic interest as well. Growth in developing countries will be the primary market for American exports and American jobs over the next decades. Most of the fastest growing export and investment markets for the United States are in former or current assistant recipient countries. There are also huge opportunities available for building infrastructure, including clean energy and telecommunications, as well as providing technical assistance.

Equally important, the American people want us to project our values abroad. They want to live in a world that’s peaceful, prosperous, democratic, and respectful of human rights and human dignity. In a changing global landscape, the generosity and humanitarian spirit of the American people is one thing that has not changed.